Part 3 of a series

In August 1990, the National Science Foundation awarded the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory to FSU — a decision that surprised many, including MIT, which had operated the Francis Bitter National Magnet Laboratory for 30 years. The original promise was vivid: a world-class scientific facility anchoring Florida’s capital city in the emerging area of magnetics.

Three decades after FSU won the competition to host the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, the scientific mission of the MagLab is undeniably successful — the lab holds multiple world records and attracts top researchers from around the globe. But in terms of local economic impact, the results have fallen short of the original vision.

So, what would success have looked like? Here are four areas where Tallahassee has not kept pace with other national lab communities — and where it still has an opportunity to improve:

1. A research park that catalyzes private-sector growth

In thriving innovation districts, anchor institutions spark the development of adjacent private-sector firms. At Los Alamos and Oak Ridge, for example, national labs are surrounded by ecosystems of federal contractors, startups, and applied research firms.

Tallahassee’s, by contrast, is dominated by public and academic entities. It mainly consists of empty lots and aging buildings, except those built by FSU which have no connection to the MagLab. As detailed in part 2, the commercialization pipeline remains underdeveloped.

2. A tech corridor with venture capital and startup activity

Florida ranks among the top ten states for total venture capital investment — but virtually none of that flows through Tallahassee. From 2012 to 2021, the state attracted over $85 billion in VC and private equity, with nearly all of it concentrated in Miami, Tampa, and Orlando.

In Tallahassee, tech-based entrepreneurship remains rare, and there are very few examples of biomedical spinoffs or next-generation materials companies directly tied to MagLab research.

3. Strategic alignment between lab, government, and infrastructure

Cities like Los Alamos and Oak Ridge benefit from coordinated local and state investment in infrastructure, workforce development, and commercialization strategies to support lab spillover.

Tallahassee lacks such alignment. Its electric grid and zoning regulations have not been meaningfully modernized to attract energy-intensive firms. And the MagLab has also failed to embrace current energy solution technologies, instead choosing to stay the course from the early 1990s on how energy is managed – which is wasteful given what is available today.

4. Brand equity and national recognition

The MagLab is recognized in the scientific community for its world-record magnets — but its national profile is surprisingly low outside of research circles.

Unlike Oak Ridge or Los Alamos, which are synonymous with scientific innovation, Tallahassee rarely markets the MagLab as a signature asset. That’s not a failure of the science — it’s a missed opportunity in branding and communications.

5. More and better energy capacity and usage

If Tallahassee ever hopes to build an innovation economy around the MagLab, a basic question must be asked: Is the city even equipped to support one?

The answer is: maybe, maybe not.

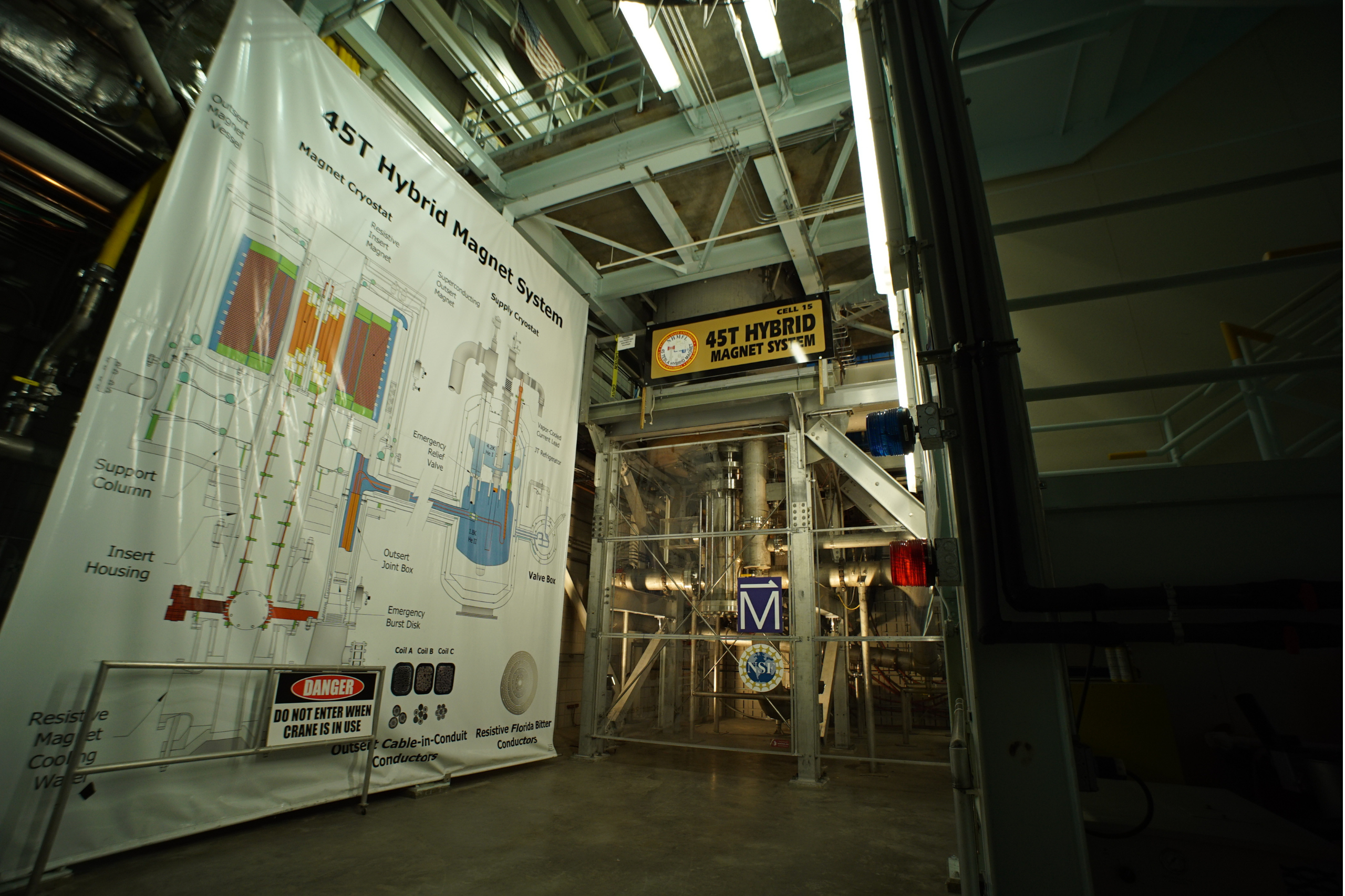

Start with electricity. The MagLab is a power-hungry facility — among the largest single energy consumers in the region. In summer 2024, reports circulated that Florida State University had been asked by the City of Tallahassee to shut down MagLab power operations for an hour due to load concerns. This raises a fundamental red flag about whether our city-owned utility can support the demands of energy-intensive research or industrial-scale commercial spinoffs.

One issue is that the MagLab is still using 1990s-era magnets that are high-energy consumers. Existing technology would make these magnets operate more efficiently and lower power consumption when it comes to cooling and powering the magnets.

The MagLab’s most powerful magnets can draw between 18 and 33 megawatts. At the upper end, that’s enough power to supply roughly 20,000 U.S. homes. Tallahassee apparently has no surplus generating capacity – where would the power come from if a new data center, battery plant, or high-wage advanced manufacturer was eyeing Tallahassee?

6. Site readiness

Beyond electricity, there’s also site readiness. Tallahassee lacks shovel-ready parcels that are truly equipped for tech-sector investment. In communities like Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, federal labs are surrounded by pre-zoned, utility-ready development pads supported by regional industrial recruitment efforts. Not so here.

Bottom line: Even if the MagLab did produce a wave of commercialization, it’s unclear whether Tallahassee could physically support the growth. Our infrastructure isn’t ready, our energy grid is strained, and our land inventory is weak.

The Good News

It’s not too late. The MagLab remains among the world’s top facilities in its field. Realizing its broader potential will require:

- A serious commercialization strategy

- Infrastructure enhancements to attract private investment

- Deliberate partnerships across academia, government, and industry

- Independent economic metrics and bold regional targets

A world-class lab deserves a world-class regional strategy. Tallahassee has a second chance — if its leaders seize it.

Coming next: Is this an FSU problem or an all-the-other-stakeholders problem?