By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

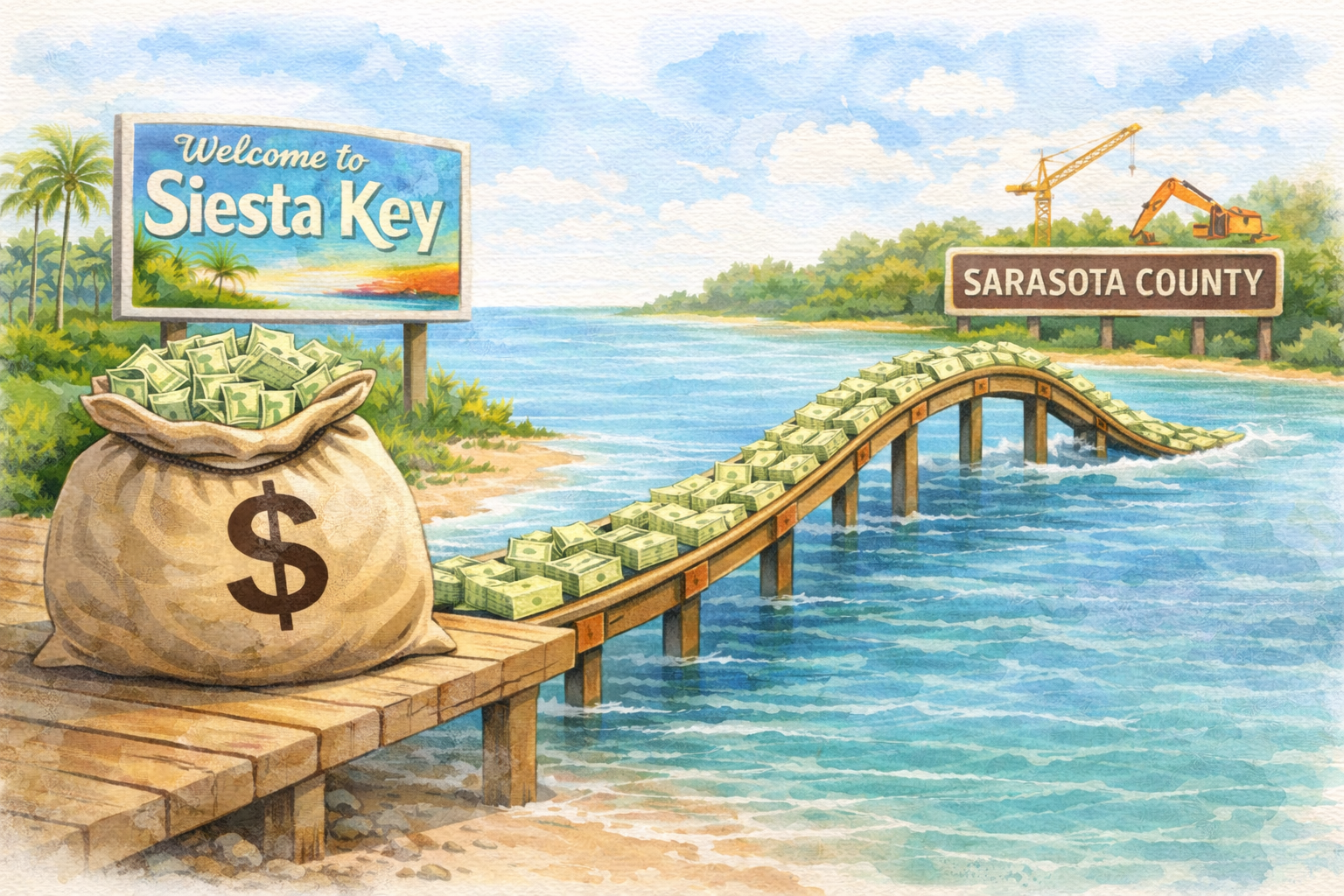

Siesta Key is a rounding error in Sarasota County’s population statistics. But when it comes to paying the county’s tourism bills, it is one of the largest contributors by far.

In a typical year, roughly one out of every four tourist-development tax dollars collected in Sarasota County comes off Siesta Key. That translates to around $13 million annually flowing from a barrier island that represents about 1.4 percent of the county’s permanent population and roughly 4 percent of its housing units.

That imbalance alone should prompt a basic question: where does the money go?

The answer is increasingly uncomfortable for county leaders — and increasingly relevant as Siesta Key property owners face tighter development restrictions, slower rebuilding approvals, and a growing political culture that celebrates saying “no” to redevelopment.

Start with the raw numbers. In fiscal year 2024, Sarasota County collected just over $48 million in tourist-development taxes, commonly known as the bed tax. Of that total, Siesta Key generated approximately 26.8 percent — the single largest share of any location in the county, ahead of even the City of Sarasota. Even after Hurricanes Helene and Milton temporarily knocked some accommodations offline, Siesta’s share in early fiscal year 2025 still hovered around 22 to 23 percent.

This is not a small contribution from a large place. It is a massive contribution from a very small one.

Yet most of those dollars are not reinvested on Siesta Key in any visible or proportional way. County policy sends bed-tax revenues into broad, countywide buckets: beach maintenance and renourishment across the entire coastline; marketing and promotion handled centrally; sports facilities and stadium debt; arts and cultural grants; and large capital projects like Nathan Benderson Park and other mainland amenities.

In plain terms, Siesta Key functions as a revenue engine whose output is largely spent elsewhere.

That imbalance is no longer theoretical — it is now playing out in real time at the County Commission.

Earlier this month, the Sarasota County Commission agreed to convene a half-day public workshop on Feb. 11 to discuss a proposed Siesta Key “beautification” initiative, following repeated requests from commissioners to move the issue up on the county’s 2026 strategic agenda. The workshop — framed by county staff as largely a listening session — comes after a new Siesta Key Beautification Alliance sought a $30 million county investment to repair and upgrade island infrastructure damaged by Hurricanes Helene and Milton.

Commissioners acknowledged both the island’s central role in generating tourist-development tax revenue and its deteriorating post-storm conditions, but stopped short of committing funding, citing looming budget gaps, revenue uncertainty, and broader countywide priorities.

This matters because, at the same time, county officials and activists routinely boast about blocking development and redevelopment on the Key — even in areas that have long been zoned for commercial or multi-family. The message to property owners is that restriction itself is a virtue, regardless of zoning, storm damage, or economic impact.

That posture is easy to maintain when someone else is paying the bills.

Tourist-development taxes are not abstract dollars. They come directly from visitors renting rooms, condos, and vacation properties — the same properties now caught in a regulatory vise. When rebuilding is delayed, discouraged, or made economically infeasible, the revenue stream county government relies on is put at risk.

The irony is hard to miss. The county depends on Siesta Key’s tourism economy to fund beach work, marketing campaigns, sports venues, and mainland projects — yet increasingly treats the island itself as a place where development should be frozen in amber.

This is not an argument for reckless building or ignoring flood risk. It is an argument for honesty and proportionality.

If Siesta Key generates roughly a quarter of Sarasota County’s bed-tax revenue, residents and property owners are justified in asking why so little of that investment visibly returns to the island itself. Why is it acceptable for Siesta to subsidize stadium debt, regional parks, and countywide promotion, while being told that responsible redevelopment on the Key is somehow a threat to the public good?

The question becomes even sharper after storms. Hurricanes don’t just damage buildings; they test whether local governments are serious about resilience. Rebuilding to modern standards, elevating structures, and replacing outdated, non-compliant buildings all cost money and require regulatory cooperation. When those efforts are slowed or blocked, the long-term risk — both physical and financial — increases.

That contribution should buy a seat at the table.

This story is not about one variance request or one development fight. It is about a structural imbalance that has gone largely unexamined: a small community generating an outsized share of public revenue, while being politically rewarded with restrictions rather than reinvestment.

Siesta Key’s tourism economy has helped carry Sarasota County through downturns, disasters, and budget cycles. It is doing so again now, even as storm impacts temporarily reduce capacity. That should buy more than rhetorical gratitude. It should buy a serious, good-faith examination of how county policies affect the people and properties that generate this revenue.

In the weeks ahead, Red Tape Florida will examine how these financial realities intersect with Sarasota County’s permitting and rebuilding decisions on Siesta Key — and what that means for recovery, property owners, and the long-term resilience of the county’s tourism economy.

For now, the numbers tell a simple story. Siesta Key pays the bill. Sarasota County decides how to spend it. And the people footing the bill are starting to ask harder questions.