OEV 2025 scoreboard: A goose egg

Why aren’t Tallahassee-Leon leaders demanding better performance from a $5-million-a-year organization that hasn’t landed a new business in 2025?[…]

November 25, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

OEV 2025 scoreboard: A goose egg

Why aren’t Tallahassee-Leon leaders demanding better performance from a $5-million-a-year organization that hasn’t landed a new business in 2025?

Special Report By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

In economic development, the scoreboard is brutally simple: Did companies choose you? Did they build here? Did they hire here? Did new paychecks land in your community? Everything else is costuming.

By that standard, the Office of Economic Vitality in Tallahassee-Leon County has posted a goose egg for 2025. Zero relocations. Zero transformative expansions. Zero net new job announcements. But you’d never know it from the steady hum of OEV newsletters — filled with conferences, expos, dashboards, “talent initiatives,” awards, rankings, and community events. All perfectly pleasant. None remotely related to landing employers.

This is exactly the kind of civic misdirection Red Tape Florida was built to expose. When process replaces product, when slogans replace substance, and when leaders congratulate the machinery rather than the outcomes — someone has to say it.

And, by the way, this red tape is expensive.

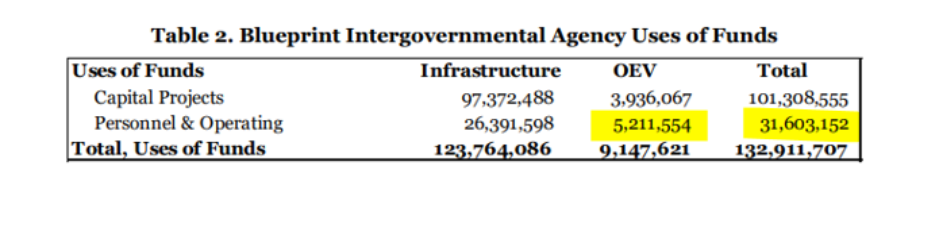

OEV carries a $5 million annual operating budget, part of the $31.6 million Blueprint budget. We are sure that money pays for hard-working folks who want to succeed. But if you track OEV’s public storytelling over the last several years, you recognize the cycle: the breathless tease, the unnamed “secret project,” the giant job number floating just over the horizon, the “exclusive” well-placed local media story hinting at transformation … and then silence. No deal. No construction. No payroll. Just a new round of teasers.

“Project Whatchamacallit”

You might be saying: Wait! Didn’t I just read about big things coming?

Indeed, in October, the breathless news: Project Vertigo “may bring 2,000 jobs to the Tallahassee airport.” A headline so aspirational it practically floated off the page. But the story was unmistakably conditional — “may,” “could,” “under consideration.” No commitments. No dates. No contracts. No site plan. Yet the public was left with the impression that a monumental win was already being loaded onto a cargo plane and taxiing toward Tallahassee.

We hope THIS is the one that gets OEV off the 2025 schneid.

But we’ve seen this show before.

In 2022, the Tallahassee Democrat ran a piece featuring a “hitlist of known, confidential projects in the pipeline.” It featured a list of 13 code-name “Projects.” So far as Red Tape Florida has found, none of them materialized

And those aren’t the only ones. Tallahassee has a long trail of “Project X” promises that never turned into payroll:

- Project Alpha – North American Aerospace Industries

• Hype: Airport cargo/teardown project at TLH, framed in Tallahassee Chamber release as a “game changer,” with estimates of roughly 700–1,000 permanent jobs, hundreds of construction jobs and ~$147–$450 million in economic impact.

• Reality: By 2024, the Tallahassee Democrat was reporting that the deal with North American Aerospace Industries had “failed to take off,” after years of cheerleading and silence from the city on its status.

- Project Bravo – TLH Cargo & Logistics Campus

• Hype: In 2022, the City of Tallahassee finalized terms with Burrell Aviation for a major cargo, logistics and aircraft-services campus at TLH — pitched as a multi-facility development that would “transform” the airport, expand the region’s air-cargo capabilities, and position Tallahassee as a southeastern aviation hub. Tallahassee Mayor John Dailey called it “the beginning of the game change.”

• Reality: By March 2024, the Tallahassee Democrat reported that the entire deal with Burrell Aviation had fallen apart — no facilities, no campus, no jobs. After nearly two years of boosterish framing, the project evaporated quietly, joining the growing list of Tallahassee airport “game changers” that never made it off the runway.

- Project Glove Story – logistics prospect at TLH

• Hype: In 2021, OEV submitted an official community response for “Project Glove Story” through the GSLI site — a logistics/warehouse prospect tied to TLH-adjacent parcels, dangling nearly $5 million in estimated incentives and flagging Tallahassee as “open for business” for a sizable operation.

• Reality: There’s been no subsequent public announcement that a Glove Story project actually chose Tallahassee, broke ground, or hired anyone. It looks like another one that lived in the pitch deck and died in the real world.

- Project E-Boat – electric-boat manufacturing concept

• Hype: Another OEV response through GSLI under the code name “Project E-Boat,” pitching Tallahassee as a site for an electric-boat related operation with the capacity to support 500+ employees within three years, again built around TLH-adjacent logistics advantages.

• Reality: Same pattern — detailed RFI response, big job potential, then radio silence. No public record of an E-Boat project choosing Tallahassee or announcing jobs here.

- Airport FTZ / IPF jobs bonanza

• Hype: Chamber/airport communications around the International Processing Facility and associated Foreign Trade Zone status tout an anticipated 1,600+ jobs and $300 million in annual economic impact once everything is up and running and the FTZ is fully utilized.

• Reality: The IPF itself is years behind its original opening timeline and the jobs/impact numbers remain projections on paper — not actual payroll in Leon County. It’s not branded as “Project [Noun],” but it fits the same pattern of huge numbers in presentations with no corresponding private-sector job creation.

It is always “big things are coming.” Somehow, the big things never quite land.

Meanwhile, the OEV weekly newsletter archive from this year, analyzed one by one by Red Tape Florida, shows an unbroken streak of zero real wins. Not a single new employer choosing Tallahassee. Not one. And yet city and county leadership remains remarkably quiet — as if failing to land a single project in 11 months is simply an unfortunate scheduling issue, not an indictment of the model.

When a win becomes a loss

Consider the high-profile “wins” Tallahassee does have on record. JetBlue lasted all of five minutes before departing. And OEV is actually touting Wawa as economic development? Delicious sandwiches, but still a gas station. These are not the kinds of economic developments you build a regional strategy around.

Yes, Amazon was a big addition … when it was announced four years ago. But insiders say that landowner Devoe Moore was as much or more responsible for the deal as anybody in government. Plus, Amazon basically picked a point on the map where it needed distribution — it wasn’t a matter of “if” but “where.” Meanwhile, OEV’s list of wins is so thin it has to claim things like a pharmacy relocation in Woodville as a victory.

While these are perfectly respectable community happenings, they are not seven-figure-ED victories. These are everyday business decisions occurring with or without government help. When your scorecard lists items that routinely happen on their own, it’s a sign the system isn’t producing anything above ordinary background business activity.

Now, to be fair, there is value associated with activities that increase the prospect pool. Securing the MDSM Magnetics Conference for the second year is a major accomplishment, as was the TakeOff Aviation Conference that was held at TLH earlier this month.

But if they don’t translate to wins, their value is diminished.

A deeply flawed system

When you examine the structure, the lack of outcomes starts making painful sense.

OEV sits inside the Blueprint Intergovernmental Agency. Under the Department of PLACE. Managed by the Intergovernmental Management Committee. With oversight and advisory input from the Economic Vitality Leadership Council, the MWSBE Citizen Advisory Committee and the Competitive Projects Cabinet. Any incentive package above roughly half-a-million dollars must go to the full IA board — all city and county commissioners — in a public meeting, unless it gets stuck earlier in the chain.

That’s five veto points before a project even touches dirt. It’s a process designed for careful deliberation, not speed — for compliance, not competitiveness. Companies choosing between Tallahassee and Alabama or Georgia can’t wait months for three committees and a workshop on a Tuesday afternoon.

Red Tape Florida has heard from multiple CEOs considering Tallahassee that there simply wasn’t enough urgency displayed by local officials. In one case, a leader actually preferred the Tallahassee market, but eventually gave up for a lack of engagement from local officials.

Meanwhile, the rest of the I-10 corridor continues racking up wins like it’s Black Friday.

• In Bay County, Oxford Technologies committed $7.5 million and 40 new aviation manufacturing jobs.

• Also in Bay County, Global Impact Products opened a 100,000-square-foot facility bringing 150 advanced manufacturing jobs — actual bodies, actually hired.

• Bay County again: Project Kilowatt, a Canadian marine manufacturer, locked in $37 million in capital investment and 285 new jobs.

• Over in Jackson County, PackEx USA is constructing a 400,000-square-foot aluminum packaging plant — $50+ million, 75 jobs.

• Santa Rosa County landed Mondelez International (Nabisco’s parent company) with a new distribution center anchoring the I-10 industrial park.

• Okaloosa County secured one of the biggest aviation projects in Florida history: Williams International’s $1-billion turbine-engine manufacturing complex, bringing more than 330 high-wage jobs.

These aren’t speculative headlines. These aren’t “projects under discussion.” These aren’t “we might, they might, someone might.” These are executed deals. Buildings. Worksites. Construction. Payroll.

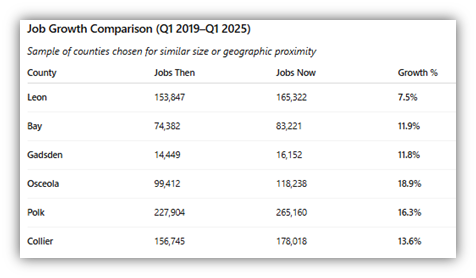

And make no mistake – this isn’t just missed opportunity – it translates to jobs … or, better put, a lack of them. Compared to similar-sized counties, or even small counties in close proximity to Leon, the county’s job growth since the start of 2019 has been anemic – just 7.5 percent growth in the past 6 years.

While others are counting new tax revenue from a growing industrial base, Leon County residents are left to chuckle at yet another Hail Mary attempt at improving the Tallahassee Airport, through an airline incentive program with projections so large and so distant you practically need binoculars to see the end date.

Spoiler alert: Until we get some economic development wins, the airport situation won’t improve.

Where is the leadership?

This piece didn’t require particularly difficult digging or an amazing sense of awareness. Everybody knows OEV isn’t working. Why the silence?

Where are local leaders, who are supposed to ask hard questions when the scoreboard reads zero? Not one commissioner, IA board member or civic stakeholder has stepped forward to publicly demand accountability for a year with no wins. We hear praise for process. We hear confidence in strategy. We do not hear the one question Tallahassee desperately needs its leaders to ask:

Where are the jobs?

Pay-for-play(ish) awards like All-America City don’t mean much when the on-the-ground results don’t include economic development and robust job growth. Tallahassee is a community laden with cheerleaders when it needs just leaders. Our local government officials would be well-advised to put down the pom poms for a few minutes and pick up a pen and start working on a new economic development structure. Perhaps the local Chamber could pitch in.

If Tallahassee wants to compete with the rest of the corridor — or anywhere — the model has to change. Economic development must be measured by outcomes, not panels. Deals need to be approved in weeks, not semesters. The mission must return to its core: recruit employers, expand employers, retain employers, produce jobs, invest capital, and report results transparently.

If it doesn’t show up on the scoreboard, it doesn’t count.

This is precisely why Red Tape Florida exists. When systems stop producing results, when leaders stop asking questions, and when the public is expected to simply believe the press releases rather than the outcomes, someone has to point to the scoreboard and tell the truth.

If we aren’t getting deals, why isn’t anyone in charge demanding them?

November 25, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

ADVOCACY: Tallahassee must stop allowing permitting officials to dodge the use of email

For months, Red Tape Florida has heard the same complaint from people who deal with Tallahassee’s permitting system: the City goes silent on email whenever things get sensitive. […]

November 19, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

ADVOCACY: Tallahassee must stop allowing permitting officials to dodge the use of email

By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

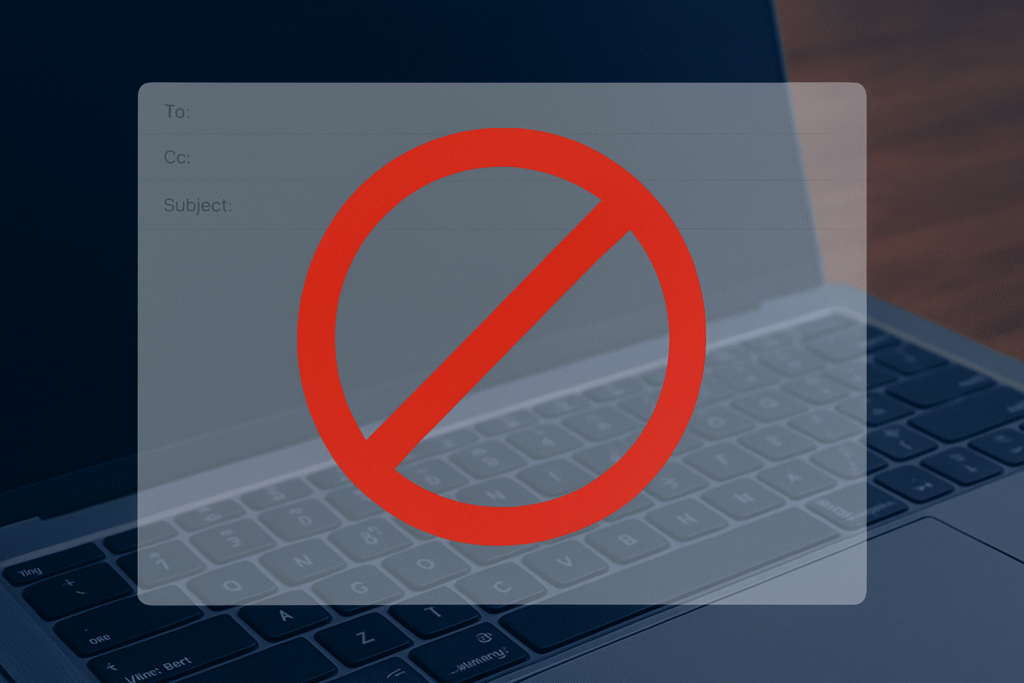

For months, Red Tape Florida has heard the same complaint from people who deal with Tallahassee’s permitting system: the City goes silent on email whenever things get sensitive.

Developers. Solar installers. Private providers. Commercial property owners. They all tell us the same thing: routine questions sometimes get answered by email, but the moment there’s a dispute, a code interpretation, a major correction, or anything controversial, staff suddenly insist on handling it by phone. No written explanation. No written directive. No written record.

This is not a customer-service quirk. It’s a transparency problem.

And it’s time for the City Commission to fix it.

What applicants are telling us

RTF has now spoken with multiple applicants who describe virtually identical experiences:

- They email the City with a detailed question about a code citation or plan review comment — and get no written answer.

- They ask for clarification on an unexpected requirement — and get a phone call instead.

- They push back on a questionable interpretation — and are told staff “can’t put that in an email.”

In the recent and now infamous “shed” case RTF covered, the City repeatedly avoided answering by email even as the applicant was told to withdraw and reapply — and threatened with daily fines. That’s not transparency. That’s control without accountability.

We are also hearing similar reports from other counties, where inspectors and plan reviewers shift sensitive issues off email specifically so the discussions are not discoverable through public records requests. RTF is looking into those cases now.

Why this matters

Permitting decisions affect property rights, construction budgets, financing, timelines, and livelihoods. When the City tells someone to change a building plan, withdraw an application, pay a new fee, redesign a structure, or face enforcement — that is the government exercising power.

Applicants deserve to know exactly what the City required and why. And the public deserves to be able to see it.

Phone-only directives make that impossible. They leave applicants guessing, private providers exposed, and citizens in the dark. They also undermine consistency: if instructions are not written down, nothing stops staff from changing the rules from applicant to applicant.

What the law expects

Florida’s public-records law is simple: communications made or received in connection with official business — including emails — are public records and must be retained. Nothing in the law says officials can avoid the public record by avoiding email. Tallahassee’s own policies acknowledge this by requiring electronic communications to be archived.

The law doesn’t force staff to use email. But it absolutely expects that the public’s business be conducted in a way that can be reviewed by the public. Directing a citizen to take costly action, with no written record, does not meet that expectation.

A fix the City Commission can implement now

RTF is calling on the Tallahassee City Commission to adopt a simple requirement:

Any material change in a permit — any directive that affects cost, timing, scope, code interpretation, classification, or potential fines — must be communicated in writing and placed in the permit file.

Staff can still use the phone for quick questions. But if it’s important enough to trigger work, cost, delay, enforcement, redesign, or legal exposure, it must be documented.

And the City should make clear that undocumented verbal instructions cannot be enforced against applicants. If it matters, write it down.

Sunshine shouldn’t disappear when a project gets complicated

The public has a right to know how decisions are made. Applicants have a right to consistency and clarity. Staff have a duty to operate in the open.

Tallahassee cannot preach transparency while allowing its most powerful permitting decisions to happen in the shadows.

RTF will continue investigating these patterns locally and elsewhere. In the meantime, the Commission can act now — by making sure that when the City wields its authority, the record reflects it.

November 19, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Special Report

There is a running joke among Florida builders that you can erect a 300-unit apartment complex faster than you can get a permit to fix a shed. It’s funny until it isn’t. […]

November 11, 2025By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Special Report

By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

There is a running joke among Florida builders that you can erect a 300-unit apartment complex faster than you can get a permit to fix a shed. It’s funny until it isn’t.

Ask Gordon Thames. Actually, don’t — he’s busy planning to demolish a perfectly functional maintenance shed because City Hall made it too expensive to keep.

Yes, demolishing. A shed. From 1989. Not because it was dangerous. Not because it violated some modern fire-code breakthrough. But because the City of Tallahassee’s building bureaucracy turned a routine renovation into a three-year maze that would embarrass Kafka.

But this isn’t just a story of unimaginable red tape. It’s a story of mistrust and misplaced priorities.

We know that because, at one point, a City of Tallahassee building official told Gordon Thames III that he “does not trust the document review from private providers.” That skepticism — not safety — became the justification for the blizzard of comments and delays that followed.

More on that later.

But first, the sorry tale of how a long-time apartment complex shed became a window into the state’s dysfunctional permitting culture.

A 35-year-old shed walks into City Hall

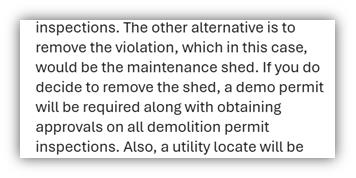

Eagles Landing Apartments were built in 1989. Like many properties of that vintage, it had two small maintenance sheds — unremarkable, functional, boring. The kind of structures that exist everywhere without incident.

In 2022, the owner, Arbor Properties, decided to refresh one. By their own admission, they assumed a permit wasn’t needed for a simple renovation. When they later attempted to get a power meter, the City pounced with a stop-work order — fair enough, rules are rules.

What followed was not enforcement — it was attrition.

The owner cleared a whopping 28 plan-review comments on a maintenance-shed renovation — that’s an entire house’s worth.

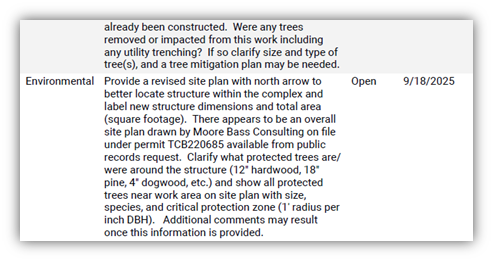

Three years later, still chasing comments

The City bounced the application, voided it, and forced a completely new permit process years later — requiring:

• New surveys

• A rain-garden plan

• Tree-mitigation calculations, even though no trees were removed — just grass behind a parking-lot curb

• Removal of a dumpster pad on the opposite side of the property

• A structural engineer to confirm 1989 concrete footers (spoiler: they’d need to X-ray them)

• A new gas-line relocation meeting

• A one-hour fire-rated wall

• And trimming part of a wall because the corner of the shed allegedly sat four inches over a property line, even after the neighbor submitted a letter saying they didn’t care.

Four inches. Thirty-five-year-old building. With neighbor consent.

And, to be clear, the “violation” wasn’t a wall or foundation — it was the roof eave extending about four inches past the setback line.

City Hall: “Never heard of it. Get out a saw.”

Meanwhile, when the owner met with the public gas team, the building inspectors reportedly crouched on their hands and knees “looking for stuff to nitpick.”

This is how you treat a developer who builds hundreds of quality housing units here?

The tree-mitigation mirage

Then came the greenest absurdity of all.

In one plan-review round, City staff demanded a full tree-mitigation plan — including a canopy calculation and protection fencing.

But as Arbor’s engineer pointed out, no trees were cut down. None. The work area was existing green space — just grass behind a curb, not a single stump in sight.

“No trees were removed as part of this project,” the engineer wrote. “Existing vegetation remains unchanged.”

Yet the tree-mitigation item stayed open through multiple rounds of review, clogging the workflow for months and forcing the owner to pay consultants to prove a negative.

For a city that brands itself as a national model of sustainability, Tallahassee somehow managed to turn phantom trees into real paperwork.

The private-provider slip

The City’s posture toward private inspections was clear from the start.

Florida law allows licensed engineers to perform reviews and inspections in place of local government — a process designed to speed construction and reduce bureaucratic load. But inside Tallahassee’s building division, private-provider work is often treated with suspicion instead of relief.

That culture of mistrust led to duplicated reviews, endless comment cycles, and what Thames calls “a moving finish line.”

Say it out loud: a City official openly admitted he doesn’t trust licensed professionals doing the same job under state statute.

There’s a word for that. It’s not “policy.”

A pattern we’ve seen before

If you think this sounds like a one-off, look west. Our work in Gulf County documented the same dynamic: projects cleared by state-licensed private inspectors got dragged back into government review, timelines stretched, and costs stacked — not for safety, but for control.

The details change, the playbook doesn’t: contradictory re-reviews, moving goalposts, and a quiet message to builders — use the lawful private-provider pathway, and expect extra friction. The net result is the same whether you’re on the coast or in the capital: fewer improvements, higher costs, and less trust.

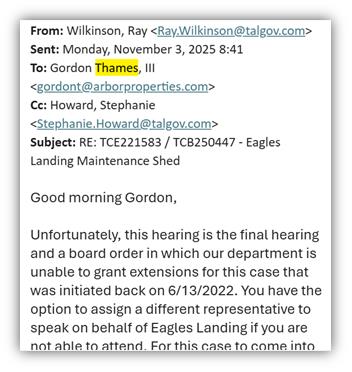

Bureaucracy vs. honeymoon

Fast forward to late 2025. The City scheduled a final code-enforcement hearing. Initially, when told that Thames would be on his honeymoon the answer was: tough luck. Eventually it was pushed it to the spring.

That moment of reason, though, came with a catch: if the owner wasn’t in compliance by a certain date, daily fines would begin — even though the delays were almost entirely caused by the building department’s own review backlog.

The absurdity of being threatened with fines for failing to meet a timeline the City itself created says everything about how the system functions.

The cheaper option: destruction

After three years of bureaucratic ping-pong, the owner realized something terrifying:

It was cheaper and faster to demolish a functioning structure than to satisfy the City’s demands. Initially, Thames was told he needed a NEW permit – a demolition permit. And, for a while, as he waited on that permit, he was facing fines for not resolving the underlying problem.

To the City’s limited credit, both Building and Code Enforcement later agreed to let Arbor demolish the shed without a demo permit — a quiet sign, perhaps, that someone inside finally recognized the overreach.

Still, think about that logic. A 35-year-old building, structurally sound and code-compliant by any reasonable measure, headed for the landfill because compliance was harder than removal.

Climate plan? Sustainability? Affordability?

Meet the permitting division.

Why it matters

This isn’t about one shed. It’s about what it says:

• Bureaucracy is prioritized over problem-solving.

• The City will destroy value before it will bend.

• Private inspection options trigger institutional defensiveness.

• Housing providers watch this and think twice about investing here.

Tallahassee’s growth strategy cannot be “annoy them until they leave.”

One question for City Hall

Is this the business climate we meant to build — or just the one we accidentally built because no one is watching the building department?

How can a city government preside over a process that literally values destruction more than improvement?

What kind of culture allows that to happen — and who’s proud of it?

For the sake of fairness, the City has shown small signs of course-correction — but the larger pattern remains: systems designed to serve are too often built to stall.

We don’t expect quick answers from those in charge at City Hall. Just the usual smirk, the shrug, and the mumble as they turn their backs on the private sector:

“Shed happens.”

November 11, 2025By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Tallahassee Reports and the price of positive coverage for the city commission majority

If you only read the headlines, you’d think the great ethics scandal in Tallahassee was… an unpaid hospital board volunteer making a campaign contribution. […]

November 7, 2025Special Report by Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Tallahassee Reports and the price of positive coverage for the city commission majority

How Tallahassee’s airport capital improvement fund subsidized friendlier coverage for the mayor and his pals – and attacks on his foes

If you only read the headlines, you’d think the great ethics scandal in Tallahassee was… an unpaid hospital board volunteer making a campaign contribution.

That’s the breathless premise of Tallahassee Reports’ Oct. 29 piece “TMH Board Member Donates to Matlow Campaign During TMH-FSU Negotiations.” The target: Sally Bradshaw — a longtime civic figure serving on the TMH board without compensation — whose family donated $3,000 to Jeremy Matlow’s campaign while TMH and FSU sparred over governance … a full five months after Matlow expressed opposition to the TMH-FSU deal.

TR framed the timing as suspicious. Here’s what it left out: Bradshaw didn’t gain a job, a contract, or any personal benefit. She is — literally — an unpaid volunteer trying to keep the community’s hospital accountable to the community. She has donated hundreds of hours to the cause, all while trying to run a local independent bookstore in the middle of an expansion.

Meanwhile, there’s a different money story Tallahassee should be talking about: the years-long pipeline of public dollars quietly routed to the nonprofit behind Tallahassee Reports — and how TR’s posture toward City Hall shifted right when those payments started.

Follow the money

Let’s pause the narrative and walk through the paper trail.

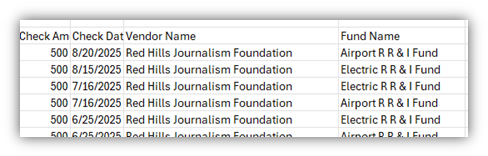

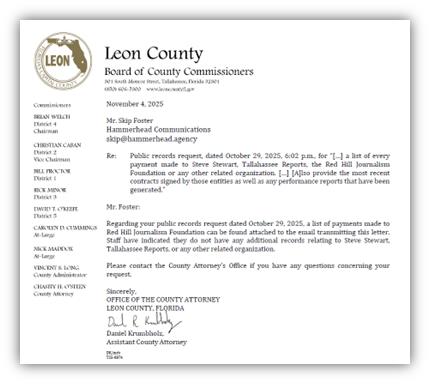

We pulled checkbook data from the City and requested public records from the County. We reviewed the fund sources. We traced where the payments went and what they were coded for. Once you see the pattern, the rest of this story stops being a theory and starts being a ledger:

• City of Tallahassee checkbook: recurring payments to the Red Hills Journalism Foundation (TR’s nonprofit), tagged to program areas like Marketing & Promotions and Energy Efficiency & DSM.

• Fund source revelation: within the City ledger, the “Fund Name” field shows Airport RR&I Fund and Electric RR&I Fund — restricted capital funds intended for runway and grid maintenance, not underwriting news coverage. (RR&I stands for renewal, replacement and improvement).

• Leon County ledger: from 2020–2025, Leon County paid the Red Hills Journalism Foundation monthly (mostly $700–$750), coded to Community & Media Relation.

Even Blueprint dollars went to Stewart, for purposes and reasons that aren’t fully clear.

In other words: airport maintenance dollars, electric utility capital funds, sales tax infrastructure funds and County communications money have flowed into the nonprofit behind Tallahassee Reports for the past five years.

Bottom line: When you total it all up, since 2020, Steve Stewart’s Red Hills Journalism Foundation has raked in $100,000 of taxpayer dollars for his website.

The Advertising vs. Subsidy distinction

Before anyone reaches for a strawman, let’s be clear about something. Local governments have long advertised in local media. When I worked at the Tallahassee Democrat, the City bought hurricane preparedness ads, public notices, legal ads, and utility conservation messages, among other things. That practice is normal, transparent, and healthy in a functioning civic ecosystem. If this were simply about the City buying display ads from Tallahassee Reports — nobody would blink.

But that is not what happened here.

In addition to conventional advertising, the City and County routed recurring payments to Tallahassee Reports’ nonprofit parent — including through the airport and electric utility “Renewal, Replacement & Improvement” (RRI) funds — capital accounts intended to maintain runways, substations, transformers, and critical infrastructure. These were not line-item display ads with rate sheets and run schedules. These were monthly transfers to a media nonprofit.

Did these happen outside traditional procurement channels? Is there a rate card? Publicly available scope? Placement report or deliverables? Red Tape Florida has public records requests pending on these questions.

So, did anything about Tallahassee Reports coverage change when the money started flowing? Did this plucky right-wing independent blog continue shining the light on all five Democrats on the Tallahassee City Commission?

You bet it did.

What changed at TR — and when

Before December 2019, TR routinely blasted the City’s “insider” culture. Then public payments began flowing. Since then, the outlet’s most aggressive “watchdog” pieces have exclusively targeted the Mayor’s opponents on the Commission while minimizing or reframing controversies that reflect poorly on senior City leadership.

We reviewed Tallahassee Reports’ City Hall coverage from 2020 to today — the period after the City began sending recurring payments to the Red Hills Journalism Foundation.

Here’s what we found:

• Multiple stories targeting the commissioners in the minority on the board (Matlow and Porter)

• A high-profile takedown of an unpaid volunteer (TMH board member Sally Bradshaw)

• Headlines repeatedly highlighting a lone dissenting vote as the narrative

• Not a single headline or lead story critically scrutinizing Mayor John Dailey, Commissioner Dianne Williams-Cox, Commissioner Curtis Richardson, or City Manager Reese Goad

To ensure fairness, we excluded routine “meeting notes” pieces and focused only on coverage that assigns blame, casts judgment, or frames political motives. The pattern was unmistakable: when Tallahassee Reports criticizes, it almost always runs in one direction.

And for the record: If anyone can surface a Tallahassee Reports story from this period that meaningfully holds the City’s ruling bloc accountable, we will gladly add it here. Patterns are strongest when they can withstand scrutiny — and this one does.

PRE-2020, it was a different story.

Check out this list of stories critical of the mayor, the city manager and their current-day allies:

- Insiders get their man: Reese Goad hired by a lame-duck City Commission (Sept. 17, 2018). Framed the manager hire as an insider play by the outgoing commission; Richardson was part of that body.

- City lobbying fees up 500 percent from 2011 to 2019. (Nov. 14, 2019). TR framed this as a sign that the current regime was being unduly influenced by the political class.

- Ceremonial vote reveals city commissioners’ views on City Manager Goad (Oct. 31, 2019). Reported Dailey calling a public “vote of confidence” for Goad—again positioning the pro-Goad majority (Dailey/Williams-Cox/Richardson) for critique.

- Who is lobbying for Reese Goad to be city manager? (July 5, 2018). Highlights the efforts of consulting firm Vancore Jones – widely known to be a key ally and advisor to Dailey and Goad – as a driving force behind the city manager search.

- Commissioner Curtis Richardson: “Are Businesses Leaving the City?” We have the answer (April 14, 2016). A story that mocks Richardson for suggesting businesses aren’t leaving the city when the data showed that they are.

And of course, there are more.

A watchdog becoming dependent on government dollars is not an abstraction — it’s a pressure system. It doesn’t need an explicit quid pro quo; it only needs a steady check and a narrowing sense of who the “real problem” is.

Bradshaw vs. the insinuation machine

Back to the Bradshaw “story.” If corruption requires someone to gain something, where’s the gain? There isn’t one. An unpaid board volunteer made a legal donation and, if anything, paid a reputational price for insisting the hospital preserve community control. The piece asserts impropriety by headline implication — and by carefully avoiding context about her non-compensated status. What Bradshaw actually did was exercise her First Amendment rights to support a candidate who had just announced for mayor.

Compare that with the TR silence around more obvious optics: the Mayor John Dailey’s Seminole Boosters money and the Doak vote

In February 2022, Mayor John Dailey supported a $20 million Blueprint contribution for FSU’s stadium. In the run-up, his political committees hauled in more than $23,000 from Seminole Boosters/FSU-affiliated donors. That timing drew calls — from media and party organizations — for him to return the money before the vote. He didn’t. He defended it. Then the funding went through.

By the way, instead of going to infrastructure and bathroom repairs, as promised, it went to a new Jumbotron.

That episode checked every optics box the Bradshaw non-story does not: private benefit to a political brand; aligned donor pool; a decisive vote for a powerful institution; the public interest questioned in real time.

Yet the “watchdog” outrage energy appears to have been rationed differently.

Take a moment and try to Google all the critical TR stories on the Mayor’s swollen coffers. I’ll wait.

Who’s paying — and from what pot — matters

The City’s choice of fund sources is the tell. Airport RR&I Fund and Electric RR&I Fund are capital renewal and replacement funds — the buckets used to maintain runways, terminals, and the electric grid. Using them to underwrite a journalism nonprofit is… novel. Those funds are supposed to keep planes safe and lights on, not buy “community coverage.”

Leon County’s payments are cleaner on paper — openly coded to Community and Media Relations — but they raise the same core question: why are public information budgets subsidizing a news outlet that increasingly trains its fire on a certain faction of the City commission instead of the government cutting the checks?

This is a textbook Red Tape Florida moment — where the machinery of government becomes a tool for insiders instead of a guardrail for taxpayers. Instead of transparent ad buys, the City tucked media payments behind fund codes and internal transfers, turning infrastructure dollars into quiet political currency. It’s bureaucracy not as public service, but as cover — a system flexible enough to reward allies and insulated enough to assume no one will ever notice.

What readers deserve, and what officials should answer

For City/County leaders:

• Who authorized using airport and electric R&R funds to pay the Red Hills Journalism Foundation? What was the procurement/legal theory

• What contracted deliverables were produced — and where are they?

• Did any official request or imply favorable coverage or targeted stories?

• Why a nonprofit transfer instead of standard ad buys with deliverables and placement reports?

Red Tape Florida has made public records requests seeking answers to these questions.

Call the thing by its name

Let’s retire the romance. Tallahassee Reports has never been “the free press” in the civics-textbook sense; it was a right-leaning outlet that held City Hall to account — until City Hall and the County started cutting checks. Now it uses public money to support … Democrats, like the mayor and his allies on the commission.

Then TR hammers other commissioners and community actors who cross the insiders’ agenda. That’s not journalism. That’s a publicly funded spin factory with a byline.

And suddenly the Bradshaw dust-up looks small. If you can funnel airport and utility funds into media influence, don’t point at an unpaid volunteer and cry “corruption.” Call it what it is: the city buying its own cheerleaders.

Bottom line

The City and County and Blueprint should end this arrangement immediately. This is such a brazen propaganda operation that 1980s Pravda “reporters” would blush.

Until that happens, conservatives who once looked to TR for alternative news should now see it for what it is – a vehicle to defend the Democrats that makeup the majority on the Tallahassee City Commission … and to attack its enemies.

November 7, 2025Special Report by Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

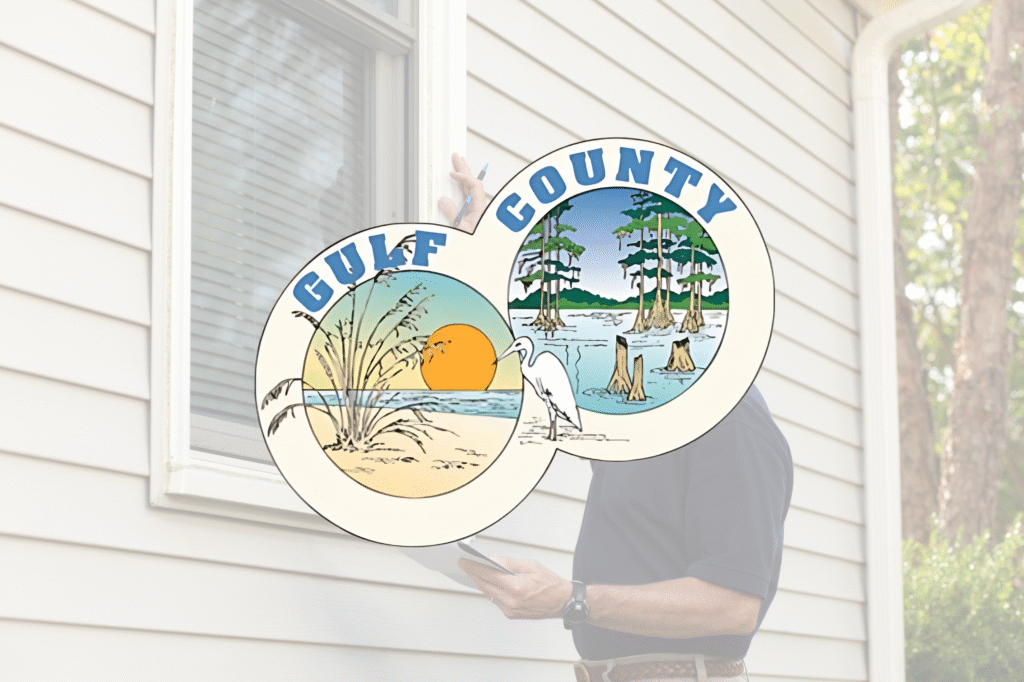

Gulf County doubles down on its $500 toll — and doubles down on being wrong

Gulf County has now responded to Red Tape Florida’s reporting on its illegal $500 “planning review fee” for builders who use private inspectors. The response, signed by County Planner Doug Crane, is exactly what you’d expect from a government caught in the act: a lot of bluster, a little jargon, and not one sentence that makes the fee legal. […]

October 24, 2025Red Tape Florida

Gulf County doubles down on its $500 toll — and doubles down on being wrong

Gulf County has now responded to Red Tape Florida’s reporting on its illegal $500 “planning review fee” for builders who use private inspectors. The response, signed by County Planner Doug Crane, is exactly what you’d expect from a government caught in the act: a lot of bluster, a little jargon, and not one sentence that makes the fee legal.

Crane’s letter lists a dozen things the county does to “safeguard health, safety and welfare” — confirming ownership, verifying setbacks, checking FEMA zones, and so on — as if this were some special service for those using private providers. The problem? The county does every one of those things already for builders who don’t use private providers. And it doesn’t charge them $500!

That’s not a “planning review.” That’s a selective surcharge, and Florida law couldn’t be clearer about it.

Under Florida Statute §553.791(2)(a):

“The local jurisdiction may not charge fees for building inspections if the fee owner or contractor hires a private provider … however, the local jurisdiction may charge a reasonable administrative fee, which shall be based on the cost that is actually incurred … for the clerical and supervisory assistance required.”

Translation: the only fee a county can impose when a private provider is used must reflect actual clerical or supervisory cost — not a made-up round number like $500 that conveniently lands in the general fund.

Then there’s §553.791(17)(a):

“A local enforcement agency, local building official, or local government may not adopt or enforce any laws, rules, procedures, policies, qualifications, or standards more stringent than those prescribed by this section.”

Gulf County’s letter literally admits it’s doing exactly that — layering its own checklist and charging an extra fee that doesn’t apply to anyone else. That’s the definition of “more stringent.”

Crane tries to justify the toll by saying it covers “staff time, documentation verification, and on-site evaluations.” Yet §553.791 says those evaluations are already part of the building process. The private provider handles inspections; the local government’s role is administrative oversight — not duplication for profit.

And remember, Gulf County is so brazen about what it’s doing it wrote it right into its code:

Let’s call this what it is: a toll for exercising a right the Legislature gave you. A $500 penalty for using a system designed to make housing more affordable and efficient. A county government that sees a reform meant to cut red tape — and adds its own roll of tape right on top.

Representative Jason Shoaf is already watching. His exclusive statement to RTF last week made that clear:

“I’m calling on all political subdivisions of the state to immediately suspend this practice and start following Florida law.”

The Legislature built a fast lane. Gulf County built a toll booth. And no matter how many bullet points the planner adds, §553.791 says what it says — and Gulf County is wrong.

October 24, 2025Red Tape Florida

FAC falling for Gulf County’s schtick on the use of private provider inspections

Here we go again: county bureaucrats who don’t like a state law are circling the wagons, slow-walking compliance, and now trying to rewrite reality to make it sound like private providers are bad for residents and business. The Florida Association of Counties’ Community & Urban Affairs Committee is pushing an agenda item dressed up as “citizen protection,” but its own packet undercuts the scare story it’s selling. […]

October 17, 2025FAC falling for Gulf County’s schtick on the use of private provider inspections

TALLAHASSEE — Here we go again: county bureaucrats who don’t like a state law are circling the wagons, slow-walking compliance, and now trying to rewrite reality to make it sound like private providers are bad for residents and business. The Florida Association of Counties’ Community & Urban Affairs Committee is pushing an agenda item dressed up as “citizen protection,” but its own packet undercuts the scare story it’s selling.

The packet’s central claim is “secrecy” — that a contractor can use a private provider without the homeowner’s knowledge. So what? Homeowners hire licensed professionals precisely to make hundreds of technical decisions they don’t micromanage — which inspector to schedule is no different from which truss detail to spec.

The use of private providers, with or without homeowner signoff, is specifically permitted in Florida statutes. Private providers are licensed, certified, and insured to the same state standards as their public-sector counterparts. We all know that the private sector almost always moves more quickly and efficiently than the government. If a homeowner wants to be notified, that’s a contract choice between owner and contractor — not a pretext for counties to kneecap a lawful option.

We’re told private providers were “designed for bigger cities” or post-hurricane spikes, as if rural counties were never in the picture. But the packet also reminds readers the Florida Building Code is meant to apply uniformly across jurisdictions and that private providers have been in statute since 2002 – that’s 23 years! Translation: this isn’t a Miami carve-out — it’s statewide policy that counties have had decades to implement.

On oversight, the sales pitch is “lack of control.” The FAC agenda item tries to bury reality in the fine print, which lists the controls: sworn plan certifications; phase-by-phase inspections; 10-business-day permit timelines after affidavit; sworn certification of code compliance upon completion; and since 2024, mandatory, published audit procedures with results posted for the public.

If “no oversight” is your talking point while you quote the oversight, maybe the talking point needs an audit.

The fiscal bogeyman is even thinner. The packet declares “devastating financial impacts” on Gulf County and its residents, offers no numbers, and then quietly notes that when an owner elects to use a private provider, the permit fee must be reduced to reflect the county’s actual cost savings — with only a reasonable administrative fee allowed. If the math is so devastating, show it. Otherwise, this reads like counties protecting fee revenue, not homeowners.

And, of course, what we know is that it’s the private sector that is taking it in the teeth on this. Gulf County is charging businesses $500 for the use of private providers – and doing absolutely nothing in return.

The legislative rundown is similar sleight of hand. The “loss of local control” language is pinned to a bill that died. The one that passed in 2025 tweaked single-trade inspections and allowed limited post-start use of providers — hardly a system meltdown. Panic without provenance is politics, not policy.

And take a look at who submitted the item: Gulf County — via Brad Bailey. Readers of Red Tape Florida will remember Bailey from our reporting on Gulf’s flat $500 “review” fee when owners chose private providers. Bailey is not a licensed plans examiner nor does he have a building code administrator license, which makes him an odd face for an anti–private provider push built on technical authority. The through-line isn’t safety — it’s bureaucracy protecting its turf.

Bottom line: Florida’s private-provider law gives owners a legal, licensed, insured alternative to the use of local building departments – who often can’t or won’t deliver timely reviews and inspections. The packet trying to kneecap that option reads like a brief for preserving status quo revenue and control — not for protecting consumers. If counties want new tools, say what and why. But stop flouting the law, stop inventing problems, and stop pretending homeowners and small builders are the threat.

FAC shouldn’t embarrass itself further by advancing this item — a straw house, built on sand by an unlicensed builder.

Here’s a better idea – tell Gulf County start following the law.

October 17, 2025

Fees are taxes in sheep’s clothing

Property-tax scrutiny is pushing cities and counties toward a quieter revenue source: fees. In theory, fees are better than taxes because they connect what you pay to what you use. In practice, many of today’s “fees” are compulsory, appear on the property-tax bill, and climb steeply — functioning like taxes by another name.[…]

October 14, 2025Red Tape Florida

Fees are taxes in sheep’s clothing

If you don’t have a choice to pay it, it’s not really a fee

Property-tax scrutiny is pushing cities and counties toward a quieter revenue source: fees. In theory, fees are better than taxes because they connect what you pay to what you use. In practice, many of today’s “fees” are compulsory, appear on the property-tax bill, and climb steeply — functioning like taxes by another name.

Start with public safety. Kissimmee just created a $150 annual fire assessment to fund a shift to a 42-hour work week and new hires; commissioners framed it as the only realistic way to cover rising costs without jacking up the millage. Nearby Ocoee doubled its fire fee from $69.50 to $139.23 per “fire protection unit,” explicitly to avoid a property-tax increase.

The Tallahassee–Leon fire-services fight hinges on the City’s push for a massive fee hike: in June, commissioners backed a roughly 22–25% increase set to take effect in September; after the County voted 5–2 to reject it, the City floated a pared-back 9.98% “Plan B,” then on Sept. 17 voted to sever the interlocal fire-services agreement.

Stormwater is on the same path. Last year Orlando approved a multiyear schedule that lifts the typical residential stormwater bill toward about $21 a month by 2028; city staff said the jump was overdue after years without increases. Oviedo adopted annual stormwater hikes through 2033 that will push typical monthly charges well over $40 to finance a backlog of projects.

If these were simply user fees, you’d pay at the counter and opt out by not using the service. That’s not how they work. Florida’s “non-ad valorem assessments” are levied by local governments, posted on the same bill as your property taxes, and collected by the tax collector. Courts have long noted that special assessments aren’t ad valorem taxes, but they can still be imposed broadly when there’s a defined “special benefit” to property. That’s why fire and stormwater assessments can reach properties that otherwise pay little or no property tax. Orlando even spells it out plainly: stormwater is billed as a non-ad valorem charge on the annual tax bill.

Meanwhile, state leaders are floating big property-tax changes for homesteads, which only increases the incentive for locals to lean on assessments and fees instead. Whether or not those Tallahassee debates go anywhere, the local shift is already happening.

Here’s the rub: calling something a “fee” doesn’t make it feel any different to the family writing the check. A doubled fire assessment and a steep stormwater hike reduce disposable income just like a millage increase would. The main difference is political optics — fees face less backlash and are easier to target, so they’ve become the preferred tool to backfill public-safety payrolls and rebuild aging pipes.

None of this argues for starving core services. Fire protection and stormwater systems are essential, and costs are rising. But honesty demands we treat compulsory assessments like what they are: tax-like charges that deserve the same transparency and accountability as any millage increase.

Three fixes would help. First, add a single “all-in burden” line on local dashboards that shows the combined annual impact of millage, assessments, and utility charges for a typical home. Second, require a true pay-for-performance link—publish the service improvements tied to each increase (response times, staffing levels, flooded-street reductions) and report against them quarterly. Third, sunset schedules automatically unless councils re-vote after a public check-in.

If local government needs more money, make the case and show the results. But let’s retire the fiction that calling it a fee makes it anything less than a tax in sheep’s clothing.

October 14, 2025Red Tape Florida

The Opportunity Still Exists — If We Want It

It’s easy to feel discouraged when examining what hasn’t materialized around the MagLab. There are no recognized clusters of private-sector R&D, no noticeable proliferation of startups, and no regional plan in place to activate this scientific powerhouse as an economic engine for North Florida. […]

September 19, 2025Red Tape Florida

The Opportunity Still Exists — If We Want It

Final part of a series

It’s easy to feel discouraged when examining what hasn’t materialized around the MagLab. There are no recognized clusters of private-sector R&D, no noticeable proliferation of startups, and no regional plan in place to activate this scientific powerhouse as an economic engine for North Florida.

But that reality is not set in stone.

The MagLab’s scientific output is elite. Its researchers are top-tier, and the facility’s presence in Tallahassee—backed by substantial NSF and state investment—is a rare asset.

And there are signs of life.

The Motor Drive Systems and Magnetics (MDSM) annual conference was held in Tallahassee for the first time this year and is returning in 2026.

Companies such as Biofront (disease testing kits) and Piersica (new battery technologies) have a toehold in Tallahassee.

What’s missing is a comprehensive strategy: a bold, shared vision among FSU, FAMU, TSC, the city, the county, state government and the business community. One that moves beyond resting on the lab’s reputation – and empty slogans like “Magnetics Capital of the World” — and actually delivers tangible results.

That means:

- FSU must open the gates — removing barriers to private-sector partnerships.

- The city must prioritize infrastructure, particularly power and site readiness for innovation-driven firms.

- The Chamber and economic development agencies must treat the MagLab as a keystone and persist when it comes to getting alignment among all the stakeholders listed above.

- And speaking of economic development, a collaboration between local government and the private sector must dramatically rework how OEV interacts with prospects to create a much higher level of agility and creativity.

- Leadership must emerge – that can convene stakeholders and tackle the issues that have led to 30 years of stagnation.

In the short term, here are 5 more quick wins that could be achieved in the next 24 months.

- Launch the MagLab Commercialization Challenge

An annual, high-visibility competition offering seed funding, lab access, and expert mentoring to startups or companies that can develop market-ready products from MagLab research. Winners commit to establishing or expanding operations in Tallahassee, turning lab breakthroughs into local jobs.

- Launch an “Innovation Sites” Map

Publish an online, publicly accessible map showing shovel-ready industrial parcels, with details on power capacity, broadband speed, and zoning — the same intel site selectors demand on day one.

- Secure a Signature Industry Partner

Land one high-visibility corporate tenant in advanced materials, clean energy, or biotech that actively uses MagLab capabilities, and announce it prominently.

- Host a National Tech + Science Summit in Tallahassee

Use the MagLab as the anchor venue for a multi-day, industry-heavy event — following the MDSM model but broadened to attract venture capital, suppliers, and manufacturing prospects.

- Set a Goal – and Achieve it

Commit to recruiting at least five MagLab-related companies and creating 250 new private-sector R&D/manufacturing jobs by the end of year two — and publish progress quarterly.

Conclusion

There is no way around it – Tallahassee’s inability to build an economy around the MagLab is a massive underachievement.

But it’s not too late to turn things around.

It starts with acknowledging how little has been done so far … and recognizing just how much is still possible through collaboration, humility, creativeness and energy.

September 19, 2025Red Tape Florida

Profit-sharing at a nonprofit? Fair’s bonus payouts, $25k signing bonus raise red flags

After Red Tape Florida first reported about the now-infamous $28,000 retirement watch, fallout was swift, with local and state officials demanding an investigation. Now, a new revelation: The incoming executive director of the Fair — who has defended the board’s decision to buy the luxury watch for her predecessor — herself received a $25,000 cash signing bonus upon being hired.[…]

September 17, 2025Red Tape Florida

Profit-sharing at a nonprofit? Fair’s bonus payouts, $25k signing bonus raise red flags

“Profit sharing” at a nonprofit.

A $25,000 signing bonus.

A salary higher than the 20-year veteran a new director replaced.

Internal documents and interviews obtained by Red Tape Florida reveal how the North Florida Fair is rewarding its leaders — and why officials are demanding answers.

After Red Tape Florida first reported about the now-infamous $28,000 retirement watch, fallout was swift, with local and state officials demanding an investigation.

Now, a new revelation: The incoming executive director of the Fair — who has defended the board’s decision to buy the luxury watch for her predecessor — herself received a $25,000 cash signing bonus upon being hired.

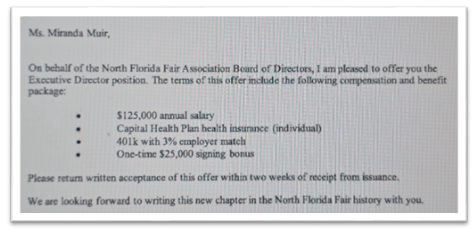

In a Dec. 5, 2024, offer letter from then-board Chair Rachel S. Pienta – who resigned in protest after the watch controversy — new fair manager Miranda Muir was offered a contract that included:

- $125,00 annual salary

- Health insurance

- 401k with 3 percent employer match

- A one-time $25,000 signing bonus

Minutes from the September 12, 2024, meeting reveal a discussion about the offer to Muir, who had been attending meetings since 2023 as the heir apparent to the director’s job and seemed a lock for the position.

While Harvey had not yet set a retirement date, the board moved toward making an offer to Muir. Initially, a base salary of $100,000 was discussed – below the long-time outgoing manager Harvey’s salary of $112,000. But board member Marcus Boston said he “went on the internet” and found a higher range

A committee was formed and there was also a mention of one-time moving expenses, but no mention of any sort of bonus. In the end, Muir received a base salary more than 10 percent higher than Harvey — and the $25,000 bonus.

Board member Steve Hurm, contacted this week by Red Tape Florida, said the board never discussed a signing bonus. “That information was never brought to me and if it had been I would have objected,” said Hurm.

Pienta declined to comment on the Muir offer saying in a statement: “I want to reiterate that it has been an honor and a privilege to serve on the North Florida Fair board over the years, including as Board President/Chair since 2024. I have stepped down from that position and will continue to focus on and strengthen our local 4-H programming and participation in the Fair moving forward.”

“Profit sharing”

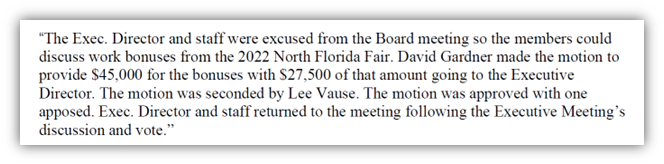

Meanwhile, the bonus money has been flowing at the fair for years and has been referred to at meetings and in minutes as “profit-sharing.”

When Hurm first heard that term he was alarmed.

“When a board member mentioned ‘profit-sharing,’ Hurm recalled, “I interrupted and said it was a nonsensical term – we’re a non-profit.”

By law, nonprofits don’t have “profits” to share. The IRS flatly prohibits it: no part of a charity’s earnings may inure to the benefit of insiders. Reasonable salaries? Sure. Profit sharing? That’s the language of Wall Street, not a 501(c)(3).

Watchdog groups warn boards constantly about even appearing to funnel surpluses to executives. Florida law is equally clear: compensation must be reasonable, but distributing income to officers is off-limits. And yet, here is a nonprofit agricultural fair association putting “profit sharing” in black and white — not whispered in a back room, but recorded as if it were standard practice.

It’s not just sloppy language. It’s a governance red flag that makes the organization look less like a community charity and more like a for-profit corporation cosplaying as one.

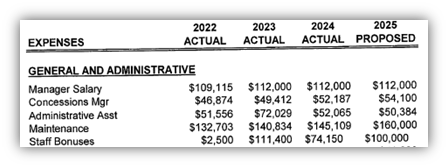

In 2023, Harvey received $27,500 in bonus money for strong performance of the annual fair. Minutes for 2024 aren’t available, but the 2025 proposed budget shows that total staff bonuses in 2024 were $74,000.

It is not clear if Harvey received a bonus this year for 2024 fair performance, but the 2025 total budget for bonuses rose to $100,000.

In the North Florida Fair’s most recent publicly available form 990 – from fiscal year 2023 – Harvey had a reported $178,000 in total compensation. Of that, according to schedule J on the form, $103,715 was base salary, $63,500 was bonuses, $7,619 was “other compensation” and $3,726 was retirement and deferred compensation.

Also that year, two board members of the non-profit were paid — $2,809 to George Kolias and $571 to Carole Abbott. The watch controversy drew withering criticism from Leon County Commissioners Bill Proctor, Christian Caban and Brian Welch at Wednesday’s meeting, while Commissioner Nick Maddox did not appear as concerned. Hanging over the issue is $30 million in proposed Blueprint funding to enhance the fairgrounds. That funding was frozen at a recent Blueprint meeting by a 9-3 vote with Tallahassee Mayor John Dailey, City Commissioner Dianne Williams-Cox and Maddox voting against.

Also a factor is Leon County’s lease with the Fair.

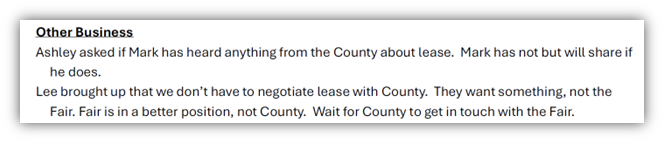

But before the retirement watch controversy broke, it was fair board members who thought they had the upper hand in negotiations with Leon County over the fair’s $1 lease.

Board member Lee Vause Jr., who remains on the board after supporting the retirement gift, was quoted in the minutes responding to a conversation about the Fair’s lease with Leon County by saying: “We don’t have to negotiate lease with County. They want something, not the Fair. Fair is in better position, not County. Wait for County to get in touch with the Fair.”

September 17, 2025Red Tape Florida

Building a MagLab ecosystem: Is it FSU’s job or a wide array of stakeholders?

Florida State University secured the bid and has drawn world-class researchers to the MagLab. It has kept the MagLab operational, but without the lavish upgrades seen elsewhere on campus (Doak Campbell Stadium, student union, etc.). The successes at the MagLab have primarily been the product of the scientists and researchers doing the actual work. […]

September 15, 2025Red Tape Florida

Building a MagLab ecosystem: Is it FSU’s job or a wide array of stakeholders?

Part 4 of a series

Florida State University secured the bid and has drawn world-class researchers to the MagLab. It has kept the MagLab operational, but without the lavish upgrades seen elsewhere on campus (Doak Campbell Stadium, student union, etc.). The successes at the MagLab have primarily been the product of the scientists and researchers doing the actual work.

And when it comes to translating that scientific prestige into broader economic benefits for Tallahassee, FSU’s role becomes more complex and, at times, restrictive.

1. The self-evaluation problem

FSU regularly publishes economic impact reports estimating the MagLab’s local annual output. However, these reports are produced by FSU’s own research center (CEFA) and rely heavily on FSU-generated spending data, rather than independently audited outcomes or private-sector-led growth.

This raises concerns about potential bias and the absence of independent validation.

2. A culture of insularity

While many universities collaborate with local stakeholders, FSU appears to operate with limited outward engagement. Although Innovation Park – over which the university now has much more control — hosts some private sector entities, it remains predominantly academic and research-focused, rather than a thriving hub of public-private innovation. And there is no way around the fact that the park’s location – save for its proximity to the airport – is not desirable.

3. Gatekeeping vs. partnering

Some business leaders feel FSU treats the MagLab as its own asset—rather than a community resource. Further, FSU does not give the MagLab its own voice to be a community resource because all the business-related deals must go through FSU-sponsored research.

These perceptions may ultimately undermine trust and deter entrepreneurial or investment opportunities.

4. No clear economic vision

FSU lacks a visible, comprehensive plan to translate the MagLab’s scientific strengths into a citywide economic strategy. Unlike institutions that launch innovation districts, venture funds, or commercialization pipelines, no comparable effort is evident here.

What Could Change

This isn’t a critique of FSU’s scientific excellence but a call for strategic recalibration. FSU should:

- Invite independent review of its economic impact claims.

- Formulate a public-private economic growth strategy centered around the MagLab.

On this point, there are numerous examples of institutions that have taken the lead. North Carolina State University’s Centennial Campus in Raleigh is a 1,300-acre, university-planned public-private research community that intentionally recruited more than 75 corporate, government, and nonprofit partners to co-locate with academic departments and research centers — creating thousands of private-sector jobs and driving Raleigh’s transformation into a tech hub. Similarly, Arizona State University’s SkySong Innovation Center redeveloped a shuttered mall into a thriving mixed-use campus housing over 80 companies, blending academic research with industry to generate sustained regional investment and employment. These projects weren’t incidental spinoffs — they were university-designed strategies to harness institutional assets for local economic growth. - Expand partnerships with private-sector firms, accelerators, and developers.

- Reposition itself not only as a scientific steward, but as a partner in regional prosperity.

If the MagLab is truly a national asset, its benefits should reach beyond campus boundaries.

And then the burden shifts to other stakeholders:

Local government: The lack of a community economic development vision is apparent to anyone paying attention. That has to change. Further, businesses that visit our market lament the bulky, clumsy structure of the Office of Economic Vitality with its unclear lines of decision-making and lack of dexterity. That has to change, too.

State government: Understandably, Tallahassee is viewed as a business-unfriendly, anti-growth, hyper-political town. But the potential of a MagLab-driven economy is too great to let those realities overcome it.

Private sector: The Chamber has simply not been effective in convening the public sector stakeholders to solve this problem. Perhaps a different group of strong business leaders is up to the challenge.

Coming next: Is it too late? (Spoiler alert: No)

September 15, 2025Red Tape Florida