What the Twin Cities tell Tallahassee/Leon about how stifling development hits home

By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

A recent Wall Street Journal analysis offers a stark, real-world lesson in housing policy — one that Tallahassee and Leon County should be studying closely.

The Journal, reporting by Rebecca Picciotto, compared two cities separated by a river but united by the same regional economy: St. Paul and Minneapolis. Same labor market. Same population pressures. Radically different housing outcomes.

The difference wasn’t developers, Wall Street, or demographic change. It was policy.

In 2022, St. Paul enacted one of the nation’s strictest rent-control ordinances, capping annual increases at 3 percent — even on vacant units, with no inflation adjustment. Minneapolis chose a different path. It avoided rent control and focused almost entirely on allowing more housing to be built, rewriting zoning and land-use rules to permit more apartments and density.

The results were immediate and dramatic.

According to HUD data cited by the Journal, apartment-building permits in St. Paul fell 79 percent in early 2022 compared with the prior year. Investment activity froze. Developers halted projects. Lenders pulled back. Property values declined by at least 6 percent. St. Paul has since been forced to roll back parts of the ordinance, exempting newer construction and reconsidering the policy altogether.

Minneapolis experienced the opposite. Apartment permits surged nearly fourfold. Downtown neighborhoods rebounded faster. New supply came online. And despite ongoing affordability challenges, rent growth in Minneapolis lagged both St. Paul and the national average during the same period.

This wasn’t a theory. It was a side-by-side governance experiment — and it validated a warning economists have been making for decades – rent controls and growth-stifling measures hurt far more than they help.

As Swedish economist Assar Lindbeck put it more than 50 years ago, “In many cases rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city — except for bombing.”

Why this matters in Tallahassee and Leon County

This matters because recent decisions in Tallahassee and Leon County point unmistakably toward the St. Paul model.

Just weeks ago, the Leon County Commission adopted changes to the comprehensive plan that further restricts where and how housing can be built. The vote was framed as smart growth and community protection. In practice, it adds friction, delay, and uncertainty — the very conditions that cause builders and lenders to pause or walk away.

Those early warning signs are already showing up locally. In a recent Tallahassee Real Estate Weekly market update, longtime Tallahassee broker and analyst Joe Manausa noted this key finding: “Homes in the lowest 25 percent climbed from roughly $147,000 in 2020 to about $210,000 in 2025. That is close to a 43 percent increase, and it represents the sharpest appreciation of any segment.”

Manausa added: “When the most affordable homes rise the fastest, tens of thousands of potential future buyers find themselves pushed farther from ownership”

At the city level, Tallahassee continues to talk about affordability while piling on layers of process, fees, discretionary review, and political veto points that make housing slower and more expensive to deliver. The language sounds pro-housing. The outcomes are not.

Good intentions don’t override incentives

One of the most revealing findings in the Journal’s reporting is how rent control altered landlord behavior. Because rent increases were capped annually and vacancy increases were banned, landlords began raising rents every year — even when they previously wouldn’t have — simply to avoid falling behind. Small owners sold. Maintenance was deferred. Investment left.

This is the part often missing from local housing debates: capital is mobile.

When government sends a signal that investment is risky, unpredictable, or politically constrained, capital doesn’t argue. It doesn’t negotiate. It goes elsewhere — often across the river.

Minneapolis understood that reality. St. Paul learned it the hard way.

Tallahassee and Leon County are now choosing which example to follow.

The choice ahead

The Wall Street Journal didn’t write about Tallahassee. But it could have.

The lesson from the Twin Cities isn’t that housing is easy, or markets are perfect. It’s that local governments can make housing crises worse — very quickly — by mistaking control for competence.

There is still time to choose a different path. One focused on supply, speed, and certainty rather than restriction and symbolism. One that acts like Minneapolis instead of St. Paul.

Because once projects stall and capital leaves, reversing course is far harder.

And by then, the damage is already done.

December 16, 2025By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Fear over facts: Leon County once again votes to make housing scarcer

Leon County residents say they want affordable housing. They say they want workforce housing. They say they want to prepare for the 42,000 new residents projected in the decades ahead. […]

December 11, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Fear over facts: Leon County once again votes to make housing scarcer

A sad tale of progressive hypocrisy; Chamber silence and a leadership void

By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Leon County residents say they want affordable housing. They say they want workforce housing. They say they want to prepare for the 42,000 new residents projected in the decades ahead.

And then, when given a chance to expand the Urban Services Area in a place planners have identified for years as a logical location for future growth — directly beside Southwood, along major arterials, with a mandatory master-planning process already required — the Leon County Commission caved to a vocal NIMBY minority and once again said no.

And as is now routine in this community, they did so with no counterproposal, no housing strategy, and no leadership from the institutions, like the Greater Tallahassee Chamber, that claim to care about affordability. That vacuum — from elected officials and from the organizations that supposedly represent economic interests — hangs over every one of these debates.

On Wednesday, a majority of county commissioners rejected a needed USA expansion.And they did so while acknowledging they have no unified plan for where future housing should go. This is policymaking driven by fear. And it is worsening a housing-supply crisis that Leon County’s own data makes painfully clear.

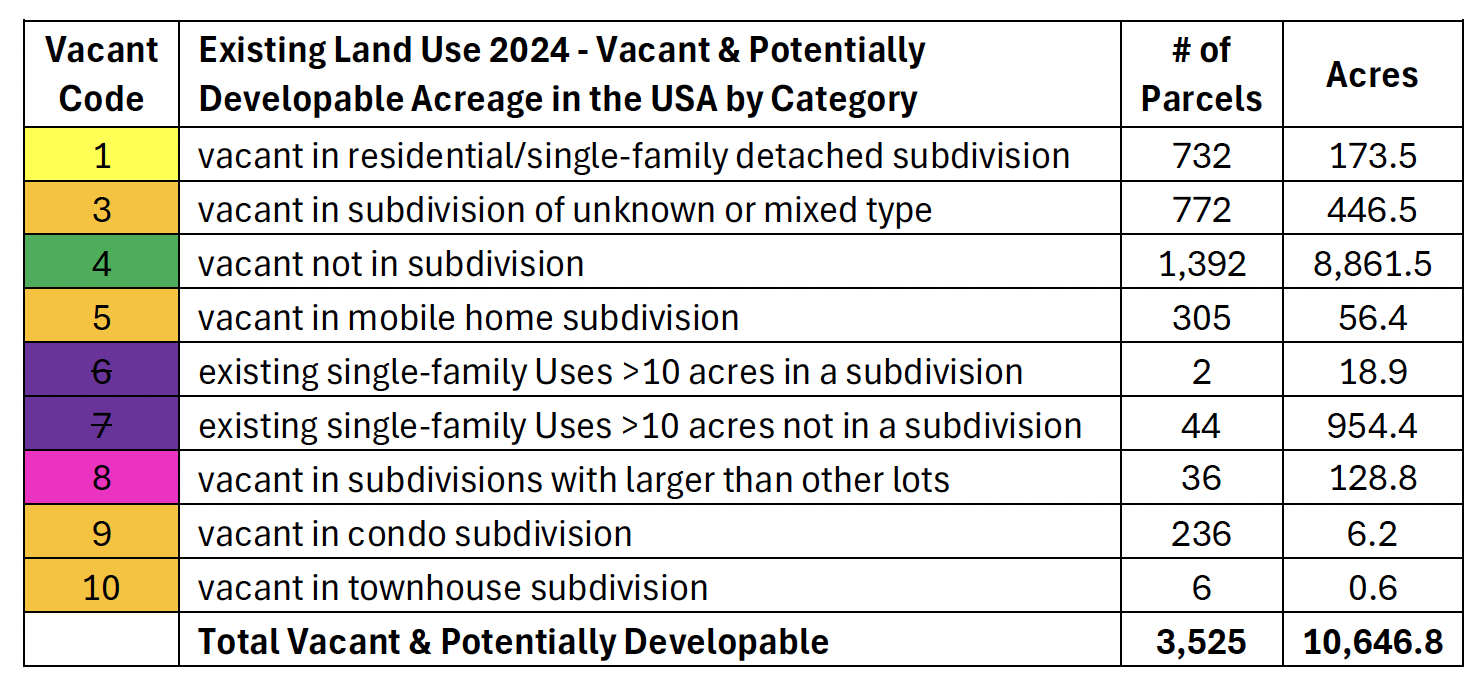

The county’s analysis of vacant and potentially developable land shows the actual supply is far more limited than advertised — only about 10,646 acres are truly viableafter accounting for environmental and regulatory constraints, and much of that land is scattered or unsuitable for meaningful housing development. Large, contiguous parcels are rare. Yet the commission just eliminated one of the few chances to build a new master-planned community on scale.

Commissioners Christian Caban, Nick Maddox and Brian Welch understood all of this — and said so plainly. Welch, in particular, gave the most honest and comprehensive explanation we have heard during this entire 30-year Comp Plan rewrite.

He began with a truth that Tallahassee’s political class works hard to avoid:

“We have to grow in this community. The biggest threat to our community is our frustration with accepting that we have to grow.”

He then dismantled the idea that this proposal was “sprawl,” noting that the land in question sits directly beside Southwood:

“You’re talking about a property directly next to Southwood, where there are 3,000 acres and 2,000 homes. To call that sprawl — and then to say infill in historic neighborhoods is also unacceptable — is a perfect encapsulation of the paralysis we are experiencing.”

Paralysis is the precise word. In Leon County, every idea becomes unacceptable:

• Infill is opposed.

• Edge-of-USA expansion is opposed.

• Mixed-use redevelopment is opposed.

• Master-planned communities are opposed.

• Density is opposed.

• Sprawl is opposed.

The impacts are predictable: rent keeps climbing, home prices keep rising, and families continue to struggle.

The anti-growth coalition is not just wrong — it is causing the affordability crisis

This is where hypocrisy becomes impossible to ignore. The same people who speak endlessly about affordable housing — who hold summits, commission studies, and lament rising rents — are the very people voting, again and again, to restrict the supply of housing.

They are not bystanders of the crisis. They are architects of it.

Leon County does not have an affordability problem because developers are building too much. It has an affordability problem because policymakers and anti-growth activists have spent twenty years making sure they build too little. Every time they kill a project, limit density, or wall off new land from the Urban Services Area, they tighten the noose around the working families they claim to champion.

This isn’t academic. It’s math. When demand rises and supply doesn’t, prices go up. And when prices go up, people get pushed out — first from homeownership, then from rentals, and eventually into housing insecurity and homelessness.

The anti-growth faction pretends these outcomes are unrelated to their decisions.

They aren’t.

Their obsession with halting development is not only worsening the housing shortage — it is directly feeding the rise in homelessness in this community.

Welch said it succinctly:

“We talk about affordable housing in the community. We have to build housing in order to create affordable housing.”

But the majority did the opposite. Again.

The leadership vacuum — especially from the Chamber

The silence at Tuesday’s meeting wasn’t just on the dais. It echoed from the organizations that claim to represent this community’s future.

Start with Commissioner Carolyn Cummings — a Chamber-backed candidate, the person business leaders were told would bring pragmatism and economic sense to the Board. She voted against housing growth

That alone should prompt some soul-searching from the Chamber. But the deeper problem is institutional:

The Chamber itself was nowhere to be found. Again.

Not at the hearing.

Not in public comments.

Not in a press release.

Not even in a social media post.

If the business community cannot speak up for housing supply — the single largest factor driving workforce shortages and pushing families out of Leon County — then what, exactly, is it for?

The anti-growth activists show up every time. They flood hearings. They pressure commissioners. They shape the narrative.

The Chamber shrugs.

Silence is a position. And on Tuesday night, silence sided with fear, stagnation and scarcity.

The only three who saw the stakes clearly

Welch, Caban and Maddox were the only commissioners who treated housing as a real policy issue rather than a political nuisance.

Welch closed with a reminder that should hang over every land-use debate:

“Everybody has a right to a home. Everybody has a right to a place to live. And we have a responsibility to facilitate that.”

Three commissioners tried to do exactly that.

The others did not.

The bottom line

Leon County says it wants affordability, opportunity and competitiveness.

But a county cannot remain affordable if it refuses to grow.

It cannot solve homelessness while restricting the supply of homes.

It cannot attract employers while driving workers out.

It cannot claim compassion while embracing policies that push families to the brink.

Until elected leaders — and the institutions that claim to represent the business community — stop treating growth as a threat rather than a necessity, nothing will change except the price of a home.

And that number is only moving in one direction.

December 11, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Ft. Walton Beach – a Florida city that might be doing code enforcement the right way

Red Tape Florida spends plenty of time calling out local governments that weaponize code enforcement. Some cities treat it as a quiet revenue stream. Others use it as a punitive tool. Many hide the entire process behind opaque notices, magistrate hearings, and a wilting stack of certified letters. […]

December 5, 2025Red Tape Florida

Ft. Walton Beach – a Florida city that might be doing code enforcement the right way

By Red Tape Florida

Red Tape Florida spends plenty of time calling out local governments that weaponize code enforcement. Some cities treat it as a quiet revenue stream. Others use it as a punitive tool. Many hide the entire process behind opaque notices, magistrate hearings, and a wilting stack of certified letters.

So when a city appears to be doing something different, it’s worth paying attention.

Fort Walton Beach is experimenting with something you rarely see anywhere in Florida: putting its code-enforcement staff directly in front of residents, explaining how the system works, and trying to resolve problems before the fines fly. Last month the city invited the public to a Community Code Enforcement Workshop at its public works complex, promising a full walkthrough of what code enforcement does, how the process works, which violations are most common, and how homeowners can avoid getting entangled in the first place.

That is unusual. Most Florida cities treat this material like it’s proprietary.

The city didn’t just hold a workshop. They also rolled out a new assistance guide aimed at helping property owners “navigate their way back into compliance.” The language they used is practically unheard of in the code-enforcement world: they want the process to be transparent. They want the public to understand how things work. And, most surprising of all, they emphasize working with residents rather than extracting fines from them.

Fort Walton Beach has also begun hosting what it calls Community Code Compliance Sweeps. In a lot of places, a “sweep” means blitzing a neighborhood and writing tickets by the dozen. But here the stated goal is different. The city says it is trying to meet residents where they are, offer guidance, and secure voluntary compliance before citations are even considered. In other words: talk first, ticket later.

Is Fort Walton Beach perfect? Of course not. Nobody knows yet whether this is a true cultural shift or just a bout of helpful messaging wrapped around the same old system. A single workshop is not proof of a transformed bureaucracy. A new pamphlet is not a guarantee that a code officer won’t still reach for the citation pad as the first resort.

But here is why this matters: if Fort Walton Beach is trying to get code enforcement right, then every other city in Florida can too. There is nothing stopping a city like Tallahassee, Jacksonville, Orlando, or Fort Myers from hosting public workshops, providing genuine assistance guides, or tracking how many cases are resolved through cooperation instead of punishment. Transparency is not prohibited by statute. Working with residents is not a radical idea.

At the least, Fort Walton Beach is a model worth studying.

At the most, it’s a shining example to which other Florida localities should aspire.

December 5, 2025Red Tape Florida

Special report: When local governments block private inspectors, consumers pay

Homeowners across Florida are being punished for doing something the Florida Legislature actually wants them to do: hire licensed private-sector inspection and plans review professionals to keep construction moving. […]

December 4, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Special report: When local governments block private inspectors, consumers pay

By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Homeowners across Florida are being punished for doing something the Florida Legislature actually wants them to do: hire licensed private-sector inspection and plans review professionals to keep construction moving.

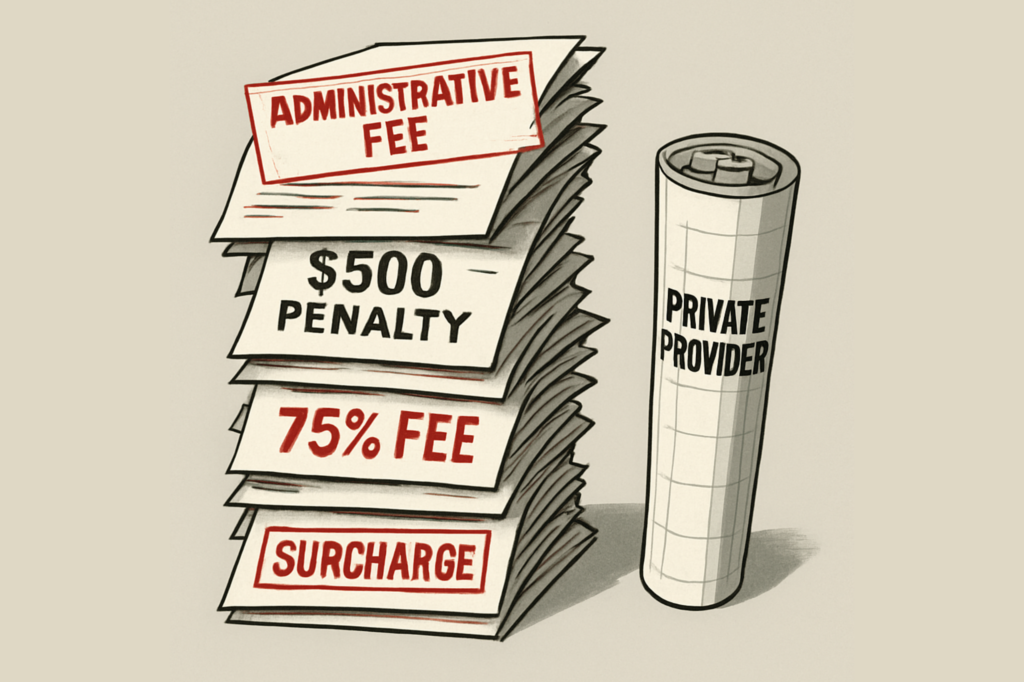

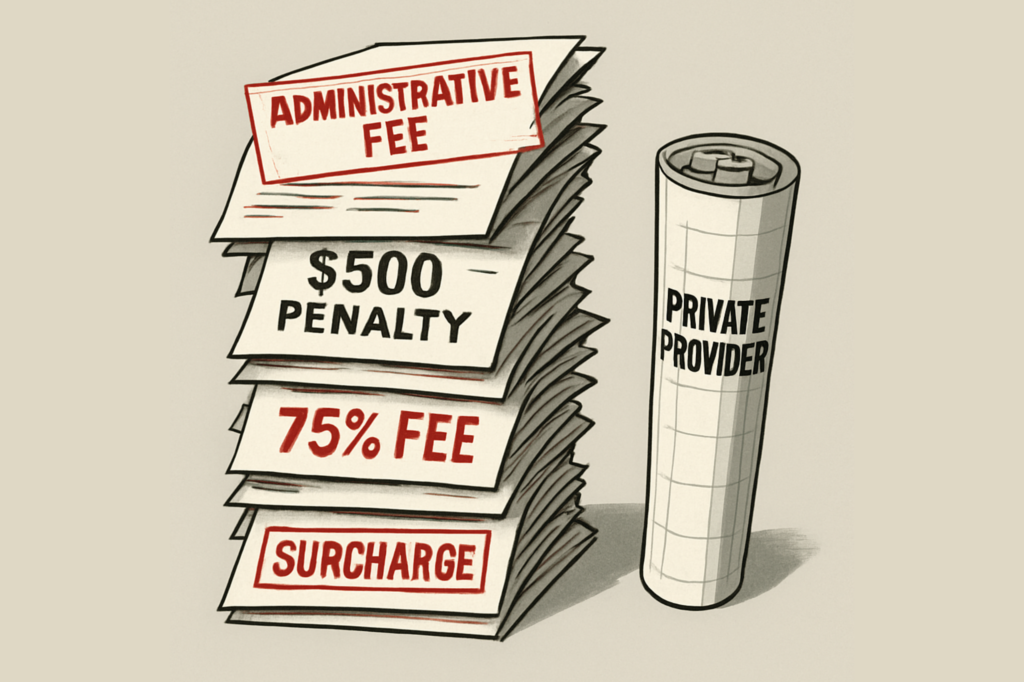

A survey of local government policy and code documents, conducted by Red Tape Florida, shows a disturbing pattern of gaming state statutes and punishing businesses who use private providers.

Instead of rewarding efficiency, far too many local governments are boldly slapping massive administrative penalties on homeowners who use private provider inspectors for plan reviews or inspections — penalties that have nothing to do with safety, nothing to do with oversight, and everything to do with protecting government revenue.

This is about bureaucracy fighting to keep its monopoly.

Florida Statute 553.791 gives homeowners the right to hire a private provider — a licensed engineer, architect, or building code professional with the same (or often higher) credentials as government inspectors, but with an actual motivation to move quickly and correctly.

Private providers exist for one reason: too many local building departments can’t keep up.

But instead of improving their performance and embracing private sector partners, some counties and cities have found a simpler strategy: punish the private sector for taking business away from them.

And the numbers prove it.

The local government list of shame

Here’s what Florida homeowners are facing when they choose a licensed private provider instead of using the local building department:

• Coral Gables: Keeps 70 to 85 percent of the permit fee even when the city performs zero plan review and zero inspections. The city refunds only 30 percent when both services are done by a private provider, and just 15 percent when inspections alone are outsourced.

• Plant City: Adds a flat $225 Private Provider Fee plus surcharges, even when the city does none of the work.

• Pinellas County: Charges a $200 base administrative fee plus 25 percent of the plan value on every private-provider permit — residential, commercial, and even inspections-only.

• Pasco County: Imposes a $600 Private Provider Administrative Fee on residential projects, clearly shown on county receipts.

• Hillsborough County: Uses a percentage-based penalty structure: 75 percent of the permit fee when plan review is done privately, 50 percent when only inspections are private, and 25 percent even when both are handled by the private provider. These charges apply even when the county performs none of the work.

• Gulf County: Adds a $500 private provider fee directly to the planning department, handwritten on the county’s plan review sheet.

FAC’s disingenuous claims

The Florida Association of Counties is now trying to spin this crisis into a story about “safety” and “fiscal impacts,” but its claims collapse under even the slightest scrutiny. In its policy document, FAC argues that private providers are “not in the best interest of public health and safety” and warns of “devastating financial impacts on Gulf County and its residents.”

None of that aligns with what is actually happening on the ground.

The financial burden in Gulf County isn’t coming from private providers — it’s coming from the county itself. Gulf County slapped a $500 private-provider fee onto the planning department base fees, directly raising construction costs for homeowners who are simply trying to move their projects forward. The same pattern exists statewide: when counties stack $500 fees, $600 surcharges, or 75-percent penalties onto private-provider work, the “devastating financial impacts” land squarely on homeowners because local governments chose to weaponize their fee schedules.

FAC’s “safety” argument collapses just as quickly. Private providers must hold the exact same state licenses as government building officials — architects, engineers, and certified code professionals — and they carry additional liability insurance. None of the opponents to private provider use have provided evidence of structures failing because of private-provider inspections. What there is, across county after county, is a pattern of chronic delays, backlogs, and bottlenecks in government inspection offices. Calling the private sector unsafe while ignoring those government failures is not consumer protection. It’s bureaucratic self-preservation.

Private sector always outperforms bureaucrats

The truth is simple: when private providers are used, projects move. When local governments fight them or bury homeowners in punitive “administrative” fees, projects stall and costs soar. FAC’s narrative tries to cast the private sector as the problem. In reality, the greatest risk — financial and otherwise — comes from counties more focused on protecting revenue than on helping citizens build safe, code-compliant homes on a reasonable timeline.

The FAC’s own justification gives the game away. Its adopted policy document admits that private providers were originally created because local governments “could not meet the demand” for plan reviews and inspections, especially during growth cycles or after hurricanes.

Unless the Legislature steps in, this war on the private sector will continue — quietly, expensively, and with real consequences for housing costs, construction timelines, and the basic fairness of Florida’s permitting system.

Time for Florida Legislature to step in

Florida doesn’t need new restrictions on private providers. It doesn’t need bureaucratic rhetoric disguised as safety. It doesn’t need to rubber-stamp FAC talking points. Florida needs lawmakers who are willing to say what counties won’t: that private-sector professionals should not be punished for doing work government offices can’t handle on time.

The good news – several legislators are doing just that. Rep. Jason Shoaf, whose district includes Gulf County, has called on local officials to explain their actions or he would determine in “further action is warranted.” Representative “Griff” Griffitts is sponsoring House Bill 405 that, among other reforms, requires building departments to discount a permit fee at least 50% when a private provider stands in the shoes of the government inspector. And at least two senators are questioning how a building department can charge a fee when an outside party performs the plans review and inspection.

The Legislature has already strengthened the private-provider system through recent reforms. Now it should finish the job.

- Reject the FAC narrative.

- Prohibit punitive fee structures including the “work around” administrative fee.

- Protect homeowners’ right to hire licensed private-sector professionals without being financially penalized for it.

Local governments have their chance to keep up. Many don’t. Florida homeowners shouldn’t be punished for choosing efficiency — and the private sector shouldn’t be the target.

The next move belongs to the Legislature. Florida’s citizens expect them to protect their choice, competition, and fairness in the permitting process.

December 4, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

ADVOCACY: Opposing growth AND being an affordable housing advocate don’t mix

If there’s one truth that emerged from our four-part interview with housing expert Dr. Sam Staley, it’s this: Florida doesn’t have a housing demand problem — it has a housing supply problem. And the reason we’re not building enough homes isn’t economics or interest rates or evil developers. It’s the result of deliberate choices made by local governments — and by the residents who pressure them.[…]

August 19, 2025Skip Foster

Red Tape Florida

ADVOCACY: Opposing growth AND being an affordable housing advocate don’t mix

If there’s one truth that emerged from our four-part interview with housing expert Dr. Sam Staley, it’s this: Florida doesn’t have a housing demand problem — it has a housing supply problem. And the reason we’re not building enough homes isn’t economics or interest rates or evil developers. It’s the result of deliberate choices made by local governments — and by the residents who pressure them.

This disconnect lies at the heart of our housing crisis. So many people — especially here in Tallahassee — claim to care deeply about affordable housing. They campaign on it. They organize around it. They pray over it.

But when someone proposes a new apartment complex or a cluster of townhomes or a modest liberalization of residential planning regulations, the tone changes. Traffic. Neighborhood character. Drainage. Trees. Suddenly, that same passion for housing gets buried under a long list of reasons why this development, in this location, is unacceptable.

That position isn’t just contradictory — it’s harmful. You cannot say you want affordable housing and then work to block the very development that creates it. Those two beliefs are incompatible.

And it defies basic laws of economics.

At last weekend’s Greater Tallahassee Chamber conference, economist Ron Hetrick shared a sobering statistic: since 2021, Tallahassee’s median home prices jumped 52 percent, to $377,000. Does anybody really think that increase isn’t connected to the city’s burdensome regulations and rabid anti-growth activism?

Opposing virtually all growth is also morally repugnant. Anti-growth advocacy leads directly to homelessness. To poverty. Simultaneously opposing growth and advocating for affordable housing is like banning umbrellas and then protesting about how wet people are.

As Staley reminded us, the data is crystal clear: Housing becomes unaffordable when supply fails to meet demand. And supply fails when cities slow-walk projects, impose overly restrictive zoning, or let NIMBY pressure grind everything to a halt. The result? Fewer places for teachers to live. Longer commutes for hospital techs. Rising rents for everyone else.

It’s time we started telling the truth about what NIMBYism costs. It is not a morally neutral stance. Every blocked project is a family that didn’t find housing. Every delayed permit is a young worker who left town. If you want to oppose development, fine — own the consequences. Don’t hide behind buzzwords like “neighborhood character” or “smart growth” while the housing shortage worsens.

Groups like the Capital Area Justice Ministry have done admirable work in drawing attention to the housing crisis. But it’s not enough to demand only public sector solutions to the problem. That movement — and others like it — must evolve to support the actual steps needed to make housing more abundant. That means higher density. That means faster permitting. That means building near existing neighborhoods.

And our local leaders — including those at the Tallahassee Chamber — need to lead with courage, not caution. For too long, public officials have deferred to the loudest voices in the room, which often represent the narrowest slice of the community. It’s time they represented everyone, including those who haven’t yet arrived — the workers, students, and families who want to live here but can’t afford to.

By the way, this is a special opportunity for progressives to show some leadership – if you want to truly show you care about the “least of these” you should be leading the charge on eliminating red tape and not letting anti-growth forces run roughshod over local policy.

Growth isn’t guaranteed in Tallahassee — and lately, it’s been in short supply. The real question is whether we want to keep turning on the red light or finally roll out the red carpet for those who would build a better future here. Dr. Staley gave us the facts. Now it’s our turn to act.

August 19, 2025Skip Foster

Red Tape Florida

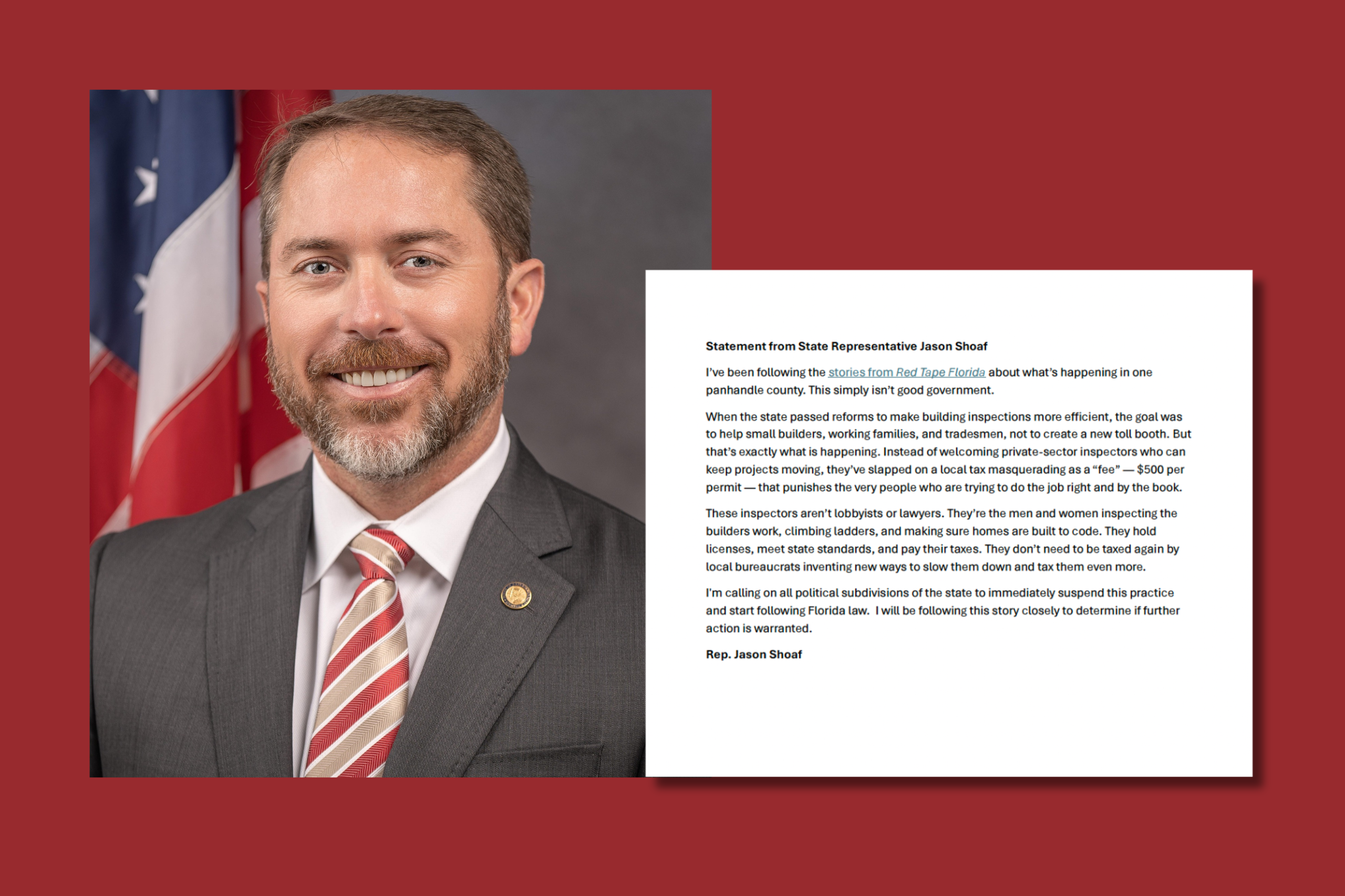

BREAKING: Rep. Jason Shoaf tells Gulf County to start following state law

State Representative Jason Shoaf is weighing in on Gulf County’s controversial $500 “administrative fee” on private building inspectors — and he’s not mincing words. In an exclusive statement to Red Tape Florida, Shoaf said the practice “isn’t good government” and urged every local government in Florida to “start following state law.” […]

October 21, 2025Red Tape Florida

BREAKING: Rep. Jason Shoaf tells Gulf County to start following state law

State Representative Jason Shoaf is weighing in on Gulf County’s controversial $500 “administrative fee” on private building inspectors — and he’s not mincing words. In an exclusive statement to Red Tape Florida, Shoaf said the practice “isn’t good government” and urged every local government in Florida to “start following state law.”

Shoaf didn’t name Gulf County directly, referring only to “one panhandle county,” but it’s clear who he’s talking about. The practice he condemns — a local government turning a state reform into a new toll booth — is exactly what Red Tape Florida has exposed.

“When the state passed reforms to make building inspections more efficient,” Shoaf said, “the goal was to help small builders, working families, and tradesmen — not to create a new toll booth. But that’s exactly what is happening.”

The state’s 2020 private-provider law was designed to keep construction moving by letting contractors use licensed third-party inspectors rather than waiting for government schedules. Gulf County’s $500 surcharge effectively punishes builders for using that option — and, as Shoaf put it, “taxes the very people who are trying to do the job right and by the book.”

“These inspectors aren’t lobbyists or lawyers,” Shoaf continued. “They’re the men and women inspecting the builders’ work, climbing ladders, and making sure homes are built to code. They hold licenses, meet state standards, and pay their taxes. They don’t need to be taxed again by local bureaucrats inventing new ways to slow them down and tax them even more.”

Shoaf’s statement marks the first public rebuke from a state official since RTF began reporting on the issue — and it sends a clear warning to other local governments considering similar schemes. It also should get the attention of the Florida Association of Counties, which has been considering Gulf County’s request to pursue a revision of the long-standing state law.

“I’m calling on all political subdivisions of the state to immediately suspend this practice and start following Florida law,” Shoaf said. “I will be following this story closely to determine if further action is warranted.”

Translation: The Legislature that opened the fast lane is watching the counties that keep putting up toll booths.

Read the full statement here.

October 21, 2025Red Tape Florida

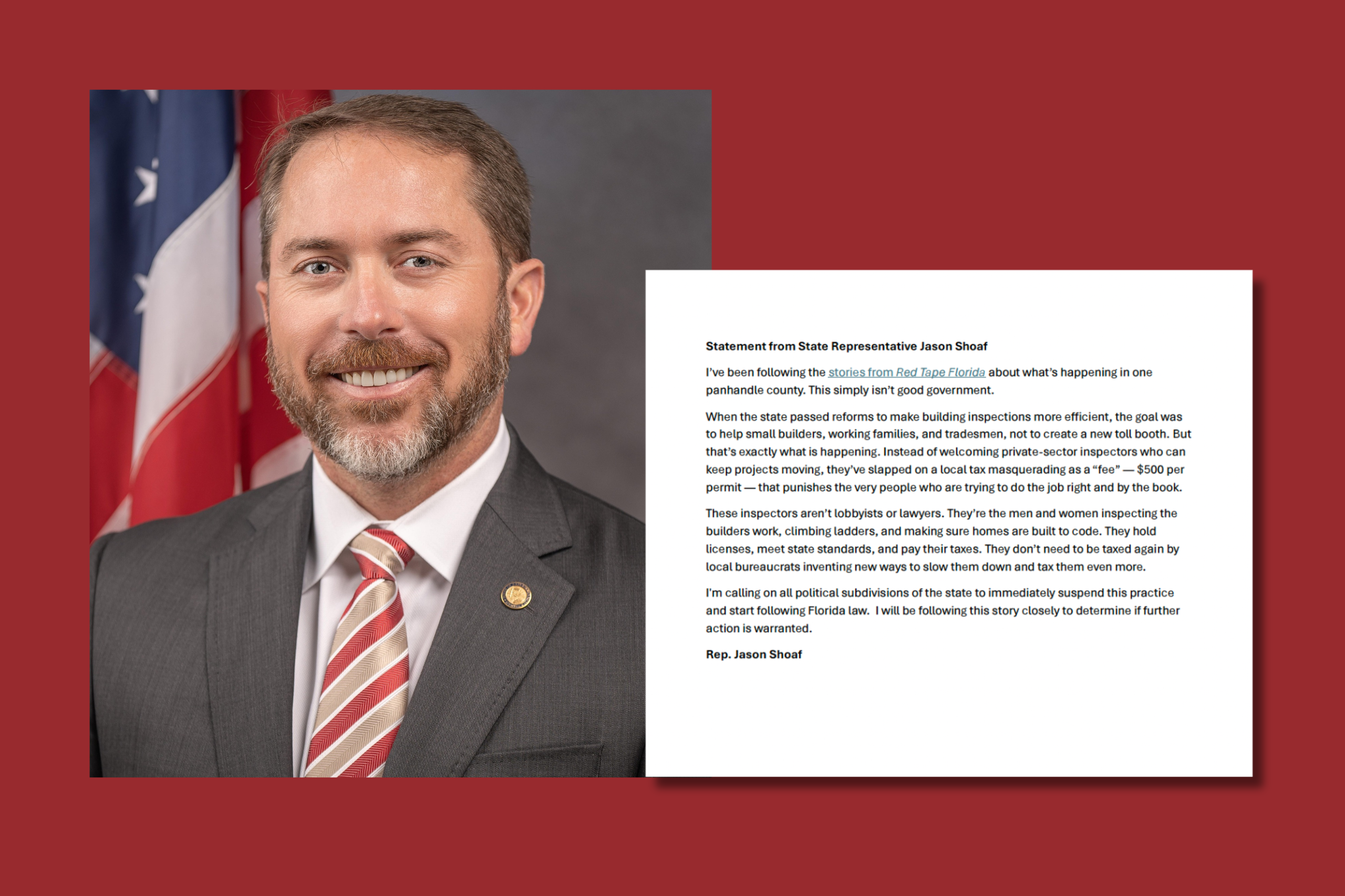

OEV 2025 scoreboard: A goose egg

Why aren’t Tallahassee-Leon leaders demanding better performance from a $5-million-a-year organization that hasn’t landed a new business in 2025?[…]

November 25, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

OEV 2025 scoreboard: A goose egg

Why aren’t Tallahassee-Leon leaders demanding better performance from a $5-million-a-year organization that hasn’t landed a new business in 2025?

Special Report By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

In economic development, the scoreboard is brutally simple: Did companies choose you? Did they build here? Did they hire here? Did new paychecks land in your community? Everything else is costuming.

By that standard, the Office of Economic Vitality in Tallahassee-Leon County has posted a goose egg for 2025. Zero relocations. Zero transformative expansions. Zero net new job announcements. But you’d never know it from the steady hum of OEV newsletters — filled with conferences, expos, dashboards, “talent initiatives,” awards, rankings, and community events. All perfectly pleasant. None remotely related to landing employers.

This is exactly the kind of civic misdirection Red Tape Florida was built to expose. When process replaces product, when slogans replace substance, and when leaders congratulate the machinery rather than the outcomes — someone has to say it.

And, by the way, this red tape is expensive.

OEV carries a $5 million annual operating budget, part of the $31.6 million Blueprint budget. We are sure that money pays for hard-working folks who want to succeed. But if you track OEV’s public storytelling over the last several years, you recognize the cycle: the breathless tease, the unnamed “secret project,” the giant job number floating just over the horizon, the “exclusive” well-placed local media story hinting at transformation … and then silence. No deal. No construction. No payroll. Just a new round of teasers.

“Project Whatchamacallit”

You might be saying: Wait! Didn’t I just read about big things coming?

Indeed, in October, the breathless news: Project Vertigo “may bring 2,000 jobs to the Tallahassee airport.” A headline so aspirational it practically floated off the page. But the story was unmistakably conditional — “may,” “could,” “under consideration.” No commitments. No dates. No contracts. No site plan. Yet the public was left with the impression that a monumental win was already being loaded onto a cargo plane and taxiing toward Tallahassee.

We hope THIS is the one that gets OEV off the 2025 schneid.

But we’ve seen this show before.

In 2022, the Tallahassee Democrat ran a piece featuring a “hitlist of known, confidential projects in the pipeline.” It featured a list of 13 code-name “Projects.” So far as Red Tape Florida has found, none of them materialized

And those aren’t the only ones. Tallahassee has a long trail of “Project X” promises that never turned into payroll:

- Project Alpha – North American Aerospace Industries

• Hype: Airport cargo/teardown project at TLH, framed in Tallahassee Chamber release as a “game changer,” with estimates of roughly 700–1,000 permanent jobs, hundreds of construction jobs and ~$147–$450 million in economic impact.

• Reality: By 2024, the Tallahassee Democrat was reporting that the deal with North American Aerospace Industries had “failed to take off,” after years of cheerleading and silence from the city on its status.

- Project Bravo – TLH Cargo & Logistics Campus

• Hype: In 2022, the City of Tallahassee finalized terms with Burrell Aviation for a major cargo, logistics and aircraft-services campus at TLH — pitched as a multi-facility development that would “transform” the airport, expand the region’s air-cargo capabilities, and position Tallahassee as a southeastern aviation hub. Tallahassee Mayor John Dailey called it “the beginning of the game change.”

• Reality: By March 2024, the Tallahassee Democrat reported that the entire deal with Burrell Aviation had fallen apart — no facilities, no campus, no jobs. After nearly two years of boosterish framing, the project evaporated quietly, joining the growing list of Tallahassee airport “game changers” that never made it off the runway.

- Project Glove Story – logistics prospect at TLH

• Hype: In 2021, OEV submitted an official community response for “Project Glove Story” through the GSLI site — a logistics/warehouse prospect tied to TLH-adjacent parcels, dangling nearly $5 million in estimated incentives and flagging Tallahassee as “open for business” for a sizable operation.

• Reality: There’s been no subsequent public announcement that a Glove Story project actually chose Tallahassee, broke ground, or hired anyone. It looks like another one that lived in the pitch deck and died in the real world.

- Project E-Boat – electric-boat manufacturing concept

• Hype: Another OEV response through GSLI under the code name “Project E-Boat,” pitching Tallahassee as a site for an electric-boat related operation with the capacity to support 500+ employees within three years, again built around TLH-adjacent logistics advantages.

• Reality: Same pattern — detailed RFI response, big job potential, then radio silence. No public record of an E-Boat project choosing Tallahassee or announcing jobs here.

- Airport FTZ / IPF jobs bonanza

• Hype: Chamber/airport communications around the International Processing Facility and associated Foreign Trade Zone status tout an anticipated 1,600+ jobs and $300 million in annual economic impact once everything is up and running and the FTZ is fully utilized.

• Reality: The IPF itself is years behind its original opening timeline and the jobs/impact numbers remain projections on paper — not actual payroll in Leon County. It’s not branded as “Project [Noun],” but it fits the same pattern of huge numbers in presentations with no corresponding private-sector job creation.

It is always “big things are coming.” Somehow, the big things never quite land.

Meanwhile, the OEV weekly newsletter archive from this year, analyzed one by one by Red Tape Florida, shows an unbroken streak of zero real wins. Not a single new employer choosing Tallahassee. Not one. And yet city and county leadership remains remarkably quiet — as if failing to land a single project in 11 months is simply an unfortunate scheduling issue, not an indictment of the model.

When a win becomes a loss

Consider the high-profile “wins” Tallahassee does have on record. JetBlue lasted all of five minutes before departing. And OEV is actually touting Wawa as economic development? Delicious sandwiches, but still a gas station. These are not the kinds of economic developments you build a regional strategy around.

Yes, Amazon was a big addition … when it was announced four years ago. But insiders say that landowner Devoe Moore was as much or more responsible for the deal as anybody in government. Plus, Amazon basically picked a point on the map where it needed distribution — it wasn’t a matter of “if” but “where.” Meanwhile, OEV’s list of wins is so thin it has to claim things like a pharmacy relocation in Woodville as a victory.

While these are perfectly respectable community happenings, they are not seven-figure-ED victories. These are everyday business decisions occurring with or without government help. When your scorecard lists items that routinely happen on their own, it’s a sign the system isn’t producing anything above ordinary background business activity.

Now, to be fair, there is value associated with activities that increase the prospect pool. Securing the MDSM Magnetics Conference for the second year is a major accomplishment, as was the TakeOff Aviation Conference that was held at TLH earlier this month.

But if they don’t translate to wins, their value is diminished.

A deeply flawed system

When you examine the structure, the lack of outcomes starts making painful sense.

OEV sits inside the Blueprint Intergovernmental Agency. Under the Department of PLACE. Managed by the Intergovernmental Management Committee. With oversight and advisory input from the Economic Vitality Leadership Council, the MWSBE Citizen Advisory Committee and the Competitive Projects Cabinet. Any incentive package above roughly half-a-million dollars must go to the full IA board — all city and county commissioners — in a public meeting, unless it gets stuck earlier in the chain.

That’s five veto points before a project even touches dirt. It’s a process designed for careful deliberation, not speed — for compliance, not competitiveness. Companies choosing between Tallahassee and Alabama or Georgia can’t wait months for three committees and a workshop on a Tuesday afternoon.

Red Tape Florida has heard from multiple CEOs considering Tallahassee that there simply wasn’t enough urgency displayed by local officials. In one case, a leader actually preferred the Tallahassee market, but eventually gave up for a lack of engagement from local officials.

Meanwhile, the rest of the I-10 corridor continues racking up wins like it’s Black Friday.

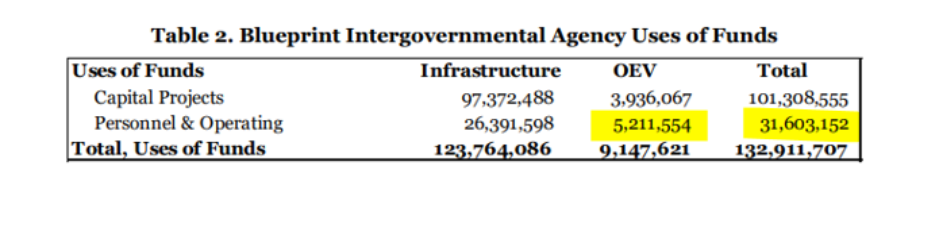

• In Bay County, Oxford Technologies committed $7.5 million and 40 new aviation manufacturing jobs.

• Also in Bay County, Global Impact Products opened a 100,000-square-foot facility bringing 150 advanced manufacturing jobs — actual bodies, actually hired.

• Bay County again: Project Kilowatt, a Canadian marine manufacturer, locked in $37 million in capital investment and 285 new jobs.

• Over in Jackson County, PackEx USA is constructing a 400,000-square-foot aluminum packaging plant — $50+ million, 75 jobs.

• Santa Rosa County landed Mondelez International (Nabisco’s parent company) with a new distribution center anchoring the I-10 industrial park.

• Okaloosa County secured one of the biggest aviation projects in Florida history: Williams International’s $1-billion turbine-engine manufacturing complex, bringing more than 330 high-wage jobs.

These aren’t speculative headlines. These aren’t “projects under discussion.” These aren’t “we might, they might, someone might.” These are executed deals. Buildings. Worksites. Construction. Payroll.

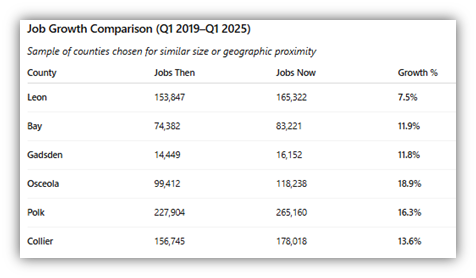

And make no mistake – this isn’t just missed opportunity – it translates to jobs … or, better put, a lack of them. Compared to similar-sized counties, or even small counties in close proximity to Leon, the county’s job growth since the start of 2019 has been anemic – just 7.5 percent growth in the past 6 years.

While others are counting new tax revenue from a growing industrial base, Leon County residents are left to chuckle at yet another Hail Mary attempt at improving the Tallahassee Airport, through an airline incentive program with projections so large and so distant you practically need binoculars to see the end date.

Spoiler alert: Until we get some economic development wins, the airport situation won’t improve.

Where is the leadership?

This piece didn’t require particularly difficult digging or an amazing sense of awareness. Everybody knows OEV isn’t working. Why the silence?

Where are local leaders, who are supposed to ask hard questions when the scoreboard reads zero? Not one commissioner, IA board member or civic stakeholder has stepped forward to publicly demand accountability for a year with no wins. We hear praise for process. We hear confidence in strategy. We do not hear the one question Tallahassee desperately needs its leaders to ask:

Where are the jobs?

Pay-for-play(ish) awards like All-America City don’t mean much when the on-the-ground results don’t include economic development and robust job growth. Tallahassee is a community laden with cheerleaders when it needs just leaders. Our local government officials would be well-advised to put down the pom poms for a few minutes and pick up a pen and start working on a new economic development structure. Perhaps the local Chamber could pitch in.

If Tallahassee wants to compete with the rest of the corridor — or anywhere — the model has to change. Economic development must be measured by outcomes, not panels. Deals need to be approved in weeks, not semesters. The mission must return to its core: recruit employers, expand employers, retain employers, produce jobs, invest capital, and report results transparently.

If it doesn’t show up on the scoreboard, it doesn’t count.

This is precisely why Red Tape Florida exists. When systems stop producing results, when leaders stop asking questions, and when the public is expected to simply believe the press releases rather than the outcomes, someone has to point to the scoreboard and tell the truth.

If we aren’t getting deals, why isn’t anyone in charge demanding them?

November 25, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

ADVOCACY: Tallahassee must stop allowing permitting officials to dodge the use of email

For months, Red Tape Florida has heard the same complaint from people who deal with Tallahassee’s permitting system: the City goes silent on email whenever things get sensitive. […]

November 19, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

ADVOCACY: Tallahassee must stop allowing permitting officials to dodge the use of email

By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

For months, Red Tape Florida has heard the same complaint from people who deal with Tallahassee’s permitting system: the City goes silent on email whenever things get sensitive.

Developers. Solar installers. Private providers. Commercial property owners. They all tell us the same thing: routine questions sometimes get answered by email, but the moment there’s a dispute, a code interpretation, a major correction, or anything controversial, staff suddenly insist on handling it by phone. No written explanation. No written directive. No written record.

This is not a customer-service quirk. It’s a transparency problem.

And it’s time for the City Commission to fix it.

What applicants are telling us

RTF has now spoken with multiple applicants who describe virtually identical experiences:

- They email the City with a detailed question about a code citation or plan review comment — and get no written answer.

- They ask for clarification on an unexpected requirement — and get a phone call instead.

- They push back on a questionable interpretation — and are told staff “can’t put that in an email.”

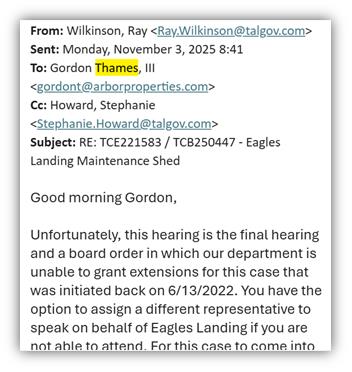

In the recent and now infamous “shed” case RTF covered, the City repeatedly avoided answering by email even as the applicant was told to withdraw and reapply — and threatened with daily fines. That’s not transparency. That’s control without accountability.

We are also hearing similar reports from other counties, where inspectors and plan reviewers shift sensitive issues off email specifically so the discussions are not discoverable through public records requests. RTF is looking into those cases now.

Why this matters

Permitting decisions affect property rights, construction budgets, financing, timelines, and livelihoods. When the City tells someone to change a building plan, withdraw an application, pay a new fee, redesign a structure, or face enforcement — that is the government exercising power.

Applicants deserve to know exactly what the City required and why. And the public deserves to be able to see it.

Phone-only directives make that impossible. They leave applicants guessing, private providers exposed, and citizens in the dark. They also undermine consistency: if instructions are not written down, nothing stops staff from changing the rules from applicant to applicant.

What the law expects

Florida’s public-records law is simple: communications made or received in connection with official business — including emails — are public records and must be retained. Nothing in the law says officials can avoid the public record by avoiding email. Tallahassee’s own policies acknowledge this by requiring electronic communications to be archived.

The law doesn’t force staff to use email. But it absolutely expects that the public’s business be conducted in a way that can be reviewed by the public. Directing a citizen to take costly action, with no written record, does not meet that expectation.

A fix the City Commission can implement now

RTF is calling on the Tallahassee City Commission to adopt a simple requirement:

Any material change in a permit — any directive that affects cost, timing, scope, code interpretation, classification, or potential fines — must be communicated in writing and placed in the permit file.

Staff can still use the phone for quick questions. But if it’s important enough to trigger work, cost, delay, enforcement, redesign, or legal exposure, it must be documented.

And the City should make clear that undocumented verbal instructions cannot be enforced against applicants. If it matters, write it down.

Sunshine shouldn’t disappear when a project gets complicated

The public has a right to know how decisions are made. Applicants have a right to consistency and clarity. Staff have a duty to operate in the open.

Tallahassee cannot preach transparency while allowing its most powerful permitting decisions to happen in the shadows.

RTF will continue investigating these patterns locally and elsewhere. In the meantime, the Commission can act now — by making sure that when the City wields its authority, the record reflects it.

November 19, 2025Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Special Report

There is a running joke among Florida builders that you can erect a 300-unit apartment complex faster than you can get a permit to fix a shed. It’s funny until it isn’t. […]

November 11, 2025By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Special Report

By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

There is a running joke among Florida builders that you can erect a 300-unit apartment complex faster than you can get a permit to fix a shed. It’s funny until it isn’t.

Ask Gordon Thames. Actually, don’t — he’s busy planning to demolish a perfectly functional maintenance shed because City Hall made it too expensive to keep.

Yes, demolishing. A shed. From 1989. Not because it was dangerous. Not because it violated some modern fire-code breakthrough. But because the City of Tallahassee’s building bureaucracy turned a routine renovation into a three-year maze that would embarrass Kafka.

But this isn’t just a story of unimaginable red tape. It’s a story of mistrust and misplaced priorities.

We know that because, at one point, a City of Tallahassee building official told Gordon Thames III that he “does not trust the document review from private providers.” That skepticism — not safety — became the justification for the blizzard of comments and delays that followed.

More on that later.

But first, the sorry tale of how a long-time apartment complex shed became a window into the state’s dysfunctional permitting culture.

A 35-year-old shed walks into City Hall

Eagles Landing Apartments were built in 1989. Like many properties of that vintage, it had two small maintenance sheds — unremarkable, functional, boring. The kind of structures that exist everywhere without incident.

In 2022, the owner, Arbor Properties, decided to refresh one. By their own admission, they assumed a permit wasn’t needed for a simple renovation. When they later attempted to get a power meter, the City pounced with a stop-work order — fair enough, rules are rules.

What followed was not enforcement — it was attrition.

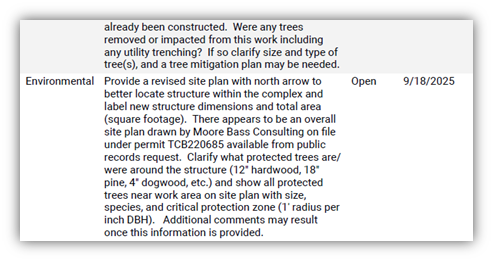

The owner cleared a whopping 28 plan-review comments on a maintenance-shed renovation — that’s an entire house’s worth.

Three years later, still chasing comments

The City bounced the application, voided it, and forced a completely new permit process years later — requiring:

• New surveys

• A rain-garden plan

• Tree-mitigation calculations, even though no trees were removed — just grass behind a parking-lot curb

• Removal of a dumpster pad on the opposite side of the property

• A structural engineer to confirm 1989 concrete footers (spoiler: they’d need to X-ray them)

• A new gas-line relocation meeting

• A one-hour fire-rated wall

• And trimming part of a wall because the corner of the shed allegedly sat four inches over a property line, even after the neighbor submitted a letter saying they didn’t care.

Four inches. Thirty-five-year-old building. With neighbor consent.

And, to be clear, the “violation” wasn’t a wall or foundation — it was the roof eave extending about four inches past the setback line.

City Hall: “Never heard of it. Get out a saw.”

Meanwhile, when the owner met with the public gas team, the building inspectors reportedly crouched on their hands and knees “looking for stuff to nitpick.”

This is how you treat a developer who builds hundreds of quality housing units here?

The tree-mitigation mirage

Then came the greenest absurdity of all.

In one plan-review round, City staff demanded a full tree-mitigation plan — including a canopy calculation and protection fencing.

But as Arbor’s engineer pointed out, no trees were cut down. None. The work area was existing green space — just grass behind a curb, not a single stump in sight.

“No trees were removed as part of this project,” the engineer wrote. “Existing vegetation remains unchanged.”

Yet the tree-mitigation item stayed open through multiple rounds of review, clogging the workflow for months and forcing the owner to pay consultants to prove a negative.

For a city that brands itself as a national model of sustainability, Tallahassee somehow managed to turn phantom trees into real paperwork.

The private-provider slip

The City’s posture toward private inspections was clear from the start.

Florida law allows licensed engineers to perform reviews and inspections in place of local government — a process designed to speed construction and reduce bureaucratic load. But inside Tallahassee’s building division, private-provider work is often treated with suspicion instead of relief.

That culture of mistrust led to duplicated reviews, endless comment cycles, and what Thames calls “a moving finish line.”

Say it out loud: a City official openly admitted he doesn’t trust licensed professionals doing the same job under state statute.

There’s a word for that. It’s not “policy.”

A pattern we’ve seen before

If you think this sounds like a one-off, look west. Our work in Gulf County documented the same dynamic: projects cleared by state-licensed private inspectors got dragged back into government review, timelines stretched, and costs stacked — not for safety, but for control.

The details change, the playbook doesn’t: contradictory re-reviews, moving goalposts, and a quiet message to builders — use the lawful private-provider pathway, and expect extra friction. The net result is the same whether you’re on the coast or in the capital: fewer improvements, higher costs, and less trust.

Bureaucracy vs. honeymoon

Fast forward to late 2025. The City scheduled a final code-enforcement hearing. Initially, when told that Thames would be on his honeymoon the answer was: tough luck. Eventually it was pushed it to the spring.

That moment of reason, though, came with a catch: if the owner wasn’t in compliance by a certain date, daily fines would begin — even though the delays were almost entirely caused by the building department’s own review backlog.

The absurdity of being threatened with fines for failing to meet a timeline the City itself created says everything about how the system functions.

The cheaper option: destruction

After three years of bureaucratic ping-pong, the owner realized something terrifying:

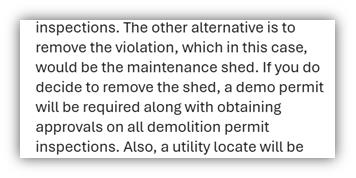

It was cheaper and faster to demolish a functioning structure than to satisfy the City’s demands. Initially, Thames was told he needed a NEW permit – a demolition permit. And, for a while, as he waited on that permit, he was facing fines for not resolving the underlying problem.

To the City’s limited credit, both Building and Code Enforcement later agreed to let Arbor demolish the shed without a demo permit — a quiet sign, perhaps, that someone inside finally recognized the overreach.

Still, think about that logic. A 35-year-old building, structurally sound and code-compliant by any reasonable measure, headed for the landfill because compliance was harder than removal.

Climate plan? Sustainability? Affordability?

Meet the permitting division.

Why it matters

This isn’t about one shed. It’s about what it says:

• Bureaucracy is prioritized over problem-solving.

• The City will destroy value before it will bend.

• Private inspection options trigger institutional defensiveness.

• Housing providers watch this and think twice about investing here.

Tallahassee’s growth strategy cannot be “annoy them until they leave.”

One question for City Hall

Is this the business climate we meant to build — or just the one we accidentally built because no one is watching the building department?

How can a city government preside over a process that literally values destruction more than improvement?

What kind of culture allows that to happen — and who’s proud of it?

For the sake of fairness, the City has shown small signs of course-correction — but the larger pattern remains: systems designed to serve are too often built to stall.

We don’t expect quick answers from those in charge at City Hall. Just the usual smirk, the shrug, and the mumble as they turn their backs on the private sector:

“Shed happens.”

November 11, 2025By Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Tallahassee Reports and the price of positive coverage for the city commission majority

If you only read the headlines, you’d think the great ethics scandal in Tallahassee was… an unpaid hospital board volunteer making a campaign contribution. […]

November 7, 2025Special Report by Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida

Tallahassee Reports and the price of positive coverage for the city commission majority

How Tallahassee’s airport capital improvement fund subsidized friendlier coverage for the mayor and his pals – and attacks on his foes

If you only read the headlines, you’d think the great ethics scandal in Tallahassee was… an unpaid hospital board volunteer making a campaign contribution.

That’s the breathless premise of Tallahassee Reports’ Oct. 29 piece “TMH Board Member Donates to Matlow Campaign During TMH-FSU Negotiations.” The target: Sally Bradshaw — a longtime civic figure serving on the TMH board without compensation — whose family donated $3,000 to Jeremy Matlow’s campaign while TMH and FSU sparred over governance … a full five months after Matlow expressed opposition to the TMH-FSU deal.

TR framed the timing as suspicious. Here’s what it left out: Bradshaw didn’t gain a job, a contract, or any personal benefit. She is — literally — an unpaid volunteer trying to keep the community’s hospital accountable to the community. She has donated hundreds of hours to the cause, all while trying to run a local independent bookstore in the middle of an expansion.

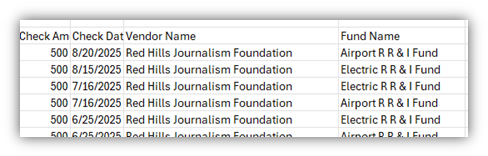

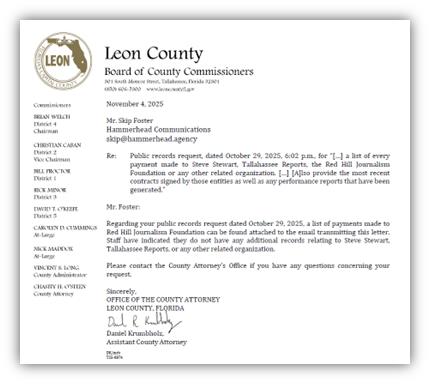

Meanwhile, there’s a different money story Tallahassee should be talking about: the years-long pipeline of public dollars quietly routed to the nonprofit behind Tallahassee Reports — and how TR’s posture toward City Hall shifted right when those payments started.

Follow the money

Let’s pause the narrative and walk through the paper trail.

We pulled checkbook data from the City and requested public records from the County. We reviewed the fund sources. We traced where the payments went and what they were coded for. Once you see the pattern, the rest of this story stops being a theory and starts being a ledger:

• City of Tallahassee checkbook: recurring payments to the Red Hills Journalism Foundation (TR’s nonprofit), tagged to program areas like Marketing & Promotions and Energy Efficiency & DSM.

• Fund source revelation: within the City ledger, the “Fund Name” field shows Airport RR&I Fund and Electric RR&I Fund — restricted capital funds intended for runway and grid maintenance, not underwriting news coverage. (RR&I stands for renewal, replacement and improvement).

• Leon County ledger: from 2020–2025, Leon County paid the Red Hills Journalism Foundation monthly (mostly $700–$750), coded to Community & Media Relation.

Even Blueprint dollars went to Stewart, for purposes and reasons that aren’t fully clear.

In other words: airport maintenance dollars, electric utility capital funds, sales tax infrastructure funds and County communications money have flowed into the nonprofit behind Tallahassee Reports for the past five years.

Bottom line: When you total it all up, since 2020, Steve Stewart’s Red Hills Journalism Foundation has raked in $100,000 of taxpayer dollars for his website.

The Advertising vs. Subsidy distinction

Before anyone reaches for a strawman, let’s be clear about something. Local governments have long advertised in local media. When I worked at the Tallahassee Democrat, the City bought hurricane preparedness ads, public notices, legal ads, and utility conservation messages, among other things. That practice is normal, transparent, and healthy in a functioning civic ecosystem. If this were simply about the City buying display ads from Tallahassee Reports — nobody would blink.

But that is not what happened here.

In addition to conventional advertising, the City and County routed recurring payments to Tallahassee Reports’ nonprofit parent — including through the airport and electric utility “Renewal, Replacement & Improvement” (RRI) funds — capital accounts intended to maintain runways, substations, transformers, and critical infrastructure. These were not line-item display ads with rate sheets and run schedules. These were monthly transfers to a media nonprofit.

Did these happen outside traditional procurement channels? Is there a rate card? Publicly available scope? Placement report or deliverables? Red Tape Florida has public records requests pending on these questions.

So, did anything about Tallahassee Reports coverage change when the money started flowing? Did this plucky right-wing independent blog continue shining the light on all five Democrats on the Tallahassee City Commission?

You bet it did.

What changed at TR — and when

Before December 2019, TR routinely blasted the City’s “insider” culture. Then public payments began flowing. Since then, the outlet’s most aggressive “watchdog” pieces have exclusively targeted the Mayor’s opponents on the Commission while minimizing or reframing controversies that reflect poorly on senior City leadership.

We reviewed Tallahassee Reports’ City Hall coverage from 2020 to today — the period after the City began sending recurring payments to the Red Hills Journalism Foundation.

Here’s what we found:

• Multiple stories targeting the commissioners in the minority on the board (Matlow and Porter)

• A high-profile takedown of an unpaid volunteer (TMH board member Sally Bradshaw)

• Headlines repeatedly highlighting a lone dissenting vote as the narrative

• Not a single headline or lead story critically scrutinizing Mayor John Dailey, Commissioner Dianne Williams-Cox, Commissioner Curtis Richardson, or City Manager Reese Goad

To ensure fairness, we excluded routine “meeting notes” pieces and focused only on coverage that assigns blame, casts judgment, or frames political motives. The pattern was unmistakable: when Tallahassee Reports criticizes, it almost always runs in one direction.

And for the record: If anyone can surface a Tallahassee Reports story from this period that meaningfully holds the City’s ruling bloc accountable, we will gladly add it here. Patterns are strongest when they can withstand scrutiny — and this one does.

PRE-2020, it was a different story.

Check out this list of stories critical of the mayor, the city manager and their current-day allies:

- Insiders get their man: Reese Goad hired by a lame-duck City Commission (Sept. 17, 2018). Framed the manager hire as an insider play by the outgoing commission; Richardson was part of that body.

- City lobbying fees up 500 percent from 2011 to 2019. (Nov. 14, 2019). TR framed this as a sign that the current regime was being unduly influenced by the political class.

- Ceremonial vote reveals city commissioners’ views on City Manager Goad (Oct. 31, 2019). Reported Dailey calling a public “vote of confidence” for Goad—again positioning the pro-Goad majority (Dailey/Williams-Cox/Richardson) for critique.

- Who is lobbying for Reese Goad to be city manager? (July 5, 2018). Highlights the efforts of consulting firm Vancore Jones – widely known to be a key ally and advisor to Dailey and Goad – as a driving force behind the city manager search.

- Commissioner Curtis Richardson: “Are Businesses Leaving the City?” We have the answer (April 14, 2016). A story that mocks Richardson for suggesting businesses aren’t leaving the city when the data showed that they are.

And of course, there are more.

A watchdog becoming dependent on government dollars is not an abstraction — it’s a pressure system. It doesn’t need an explicit quid pro quo; it only needs a steady check and a narrowing sense of who the “real problem” is.

Bradshaw vs. the insinuation machine

Back to the Bradshaw “story.” If corruption requires someone to gain something, where’s the gain? There isn’t one. An unpaid board volunteer made a legal donation and, if anything, paid a reputational price for insisting the hospital preserve community control. The piece asserts impropriety by headline implication — and by carefully avoiding context about her non-compensated status. What Bradshaw actually did was exercise her First Amendment rights to support a candidate who had just announced for mayor.

Compare that with the TR silence around more obvious optics: the Mayor John Dailey’s Seminole Boosters money and the Doak vote

In February 2022, Mayor John Dailey supported a $20 million Blueprint contribution for FSU’s stadium. In the run-up, his political committees hauled in more than $23,000 from Seminole Boosters/FSU-affiliated donors. That timing drew calls — from media and party organizations — for him to return the money before the vote. He didn’t. He defended it. Then the funding went through.

By the way, instead of going to infrastructure and bathroom repairs, as promised, it went to a new Jumbotron.

That episode checked every optics box the Bradshaw non-story does not: private benefit to a political brand; aligned donor pool; a decisive vote for a powerful institution; the public interest questioned in real time.

Yet the “watchdog” outrage energy appears to have been rationed differently.

Take a moment and try to Google all the critical TR stories on the Mayor’s swollen coffers. I’ll wait.

Who’s paying — and from what pot — matters

The City’s choice of fund sources is the tell. Airport RR&I Fund and Electric RR&I Fund are capital renewal and replacement funds — the buckets used to maintain runways, terminals, and the electric grid. Using them to underwrite a journalism nonprofit is… novel. Those funds are supposed to keep planes safe and lights on, not buy “community coverage.”

Leon County’s payments are cleaner on paper — openly coded to Community and Media Relations — but they raise the same core question: why are public information budgets subsidizing a news outlet that increasingly trains its fire on a certain faction of the City commission instead of the government cutting the checks?

This is a textbook Red Tape Florida moment — where the machinery of government becomes a tool for insiders instead of a guardrail for taxpayers. Instead of transparent ad buys, the City tucked media payments behind fund codes and internal transfers, turning infrastructure dollars into quiet political currency. It’s bureaucracy not as public service, but as cover — a system flexible enough to reward allies and insulated enough to assume no one will ever notice.

What readers deserve, and what officials should answer

For City/County leaders:

• Who authorized using airport and electric R&R funds to pay the Red Hills Journalism Foundation? What was the procurement/legal theory

• What contracted deliverables were produced — and where are they?

• Did any official request or imply favorable coverage or targeted stories?

• Why a nonprofit transfer instead of standard ad buys with deliverables and placement reports?

Red Tape Florida has made public records requests seeking answers to these questions.

Call the thing by its name

Let’s retire the romance. Tallahassee Reports has never been “the free press” in the civics-textbook sense; it was a right-leaning outlet that held City Hall to account — until City Hall and the County started cutting checks. Now it uses public money to support … Democrats, like the mayor and his allies on the commission.

Then TR hammers other commissioners and community actors who cross the insiders’ agenda. That’s not journalism. That’s a publicly funded spin factory with a byline.

And suddenly the Bradshaw dust-up looks small. If you can funnel airport and utility funds into media influence, don’t point at an unpaid volunteer and cry “corruption.” Call it what it is: the city buying its own cheerleaders.

Bottom line

The City and County and Blueprint should end this arrangement immediately. This is such a brazen propaganda operation that 1980s Pravda “reporters” would blush.

Until that happens, conservatives who once looked to TR for alternative news should now see it for what it is – a vehicle to defend the Democrats that makeup the majority on the Tallahassee City Commission … and to attack its enemies.

November 7, 2025Special Report by Skip Foster, Red Tape Florida